Did Mahler base his songs on his life?

door Roeland Hazendonk 19 apr. 2025 19 april 2025

Do Mahler’s songs reflect his journey through life and his innermost feelings? The relationship between Mahler’s life and work is full of paradoxes, making it quintessentially Mahleresque.

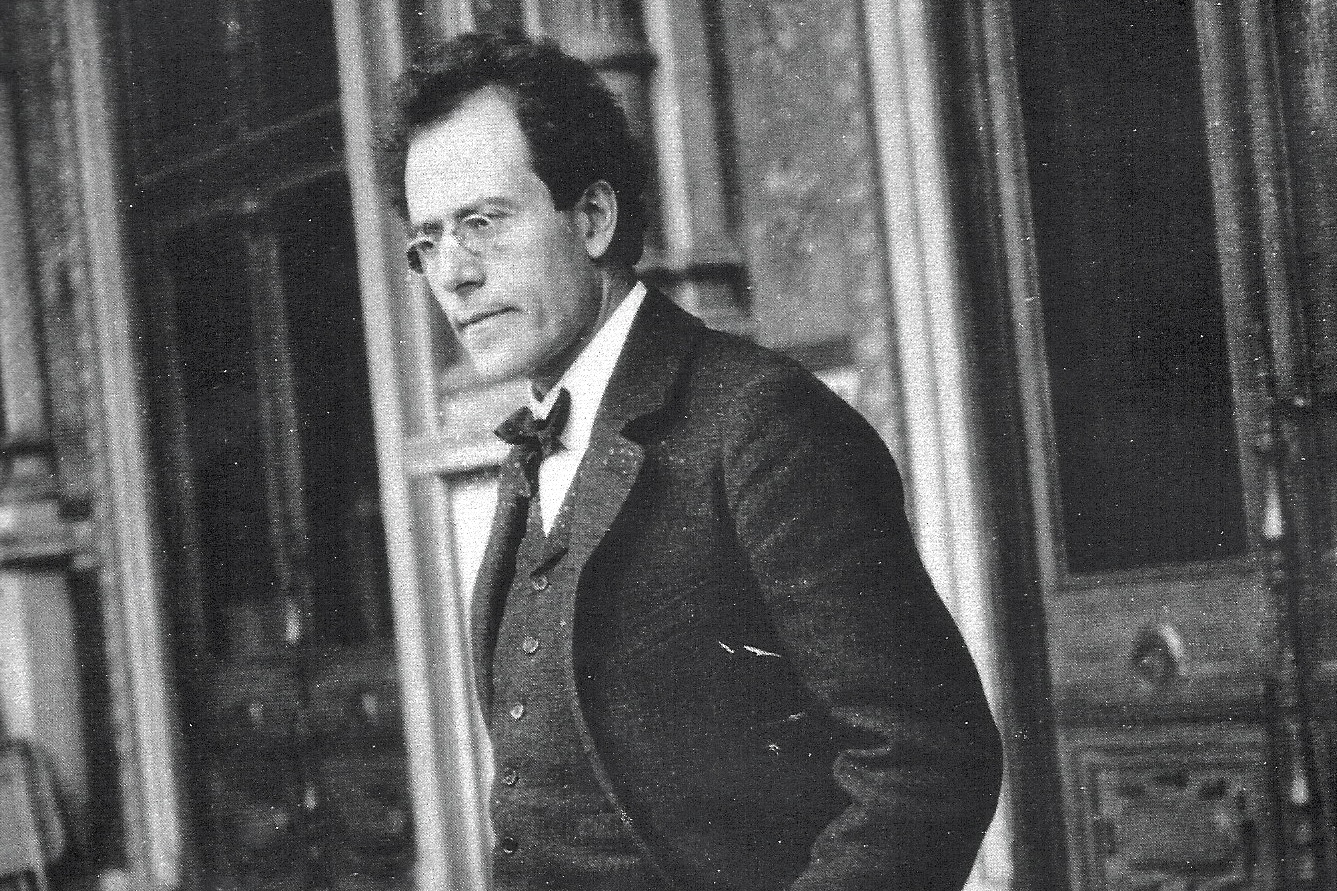

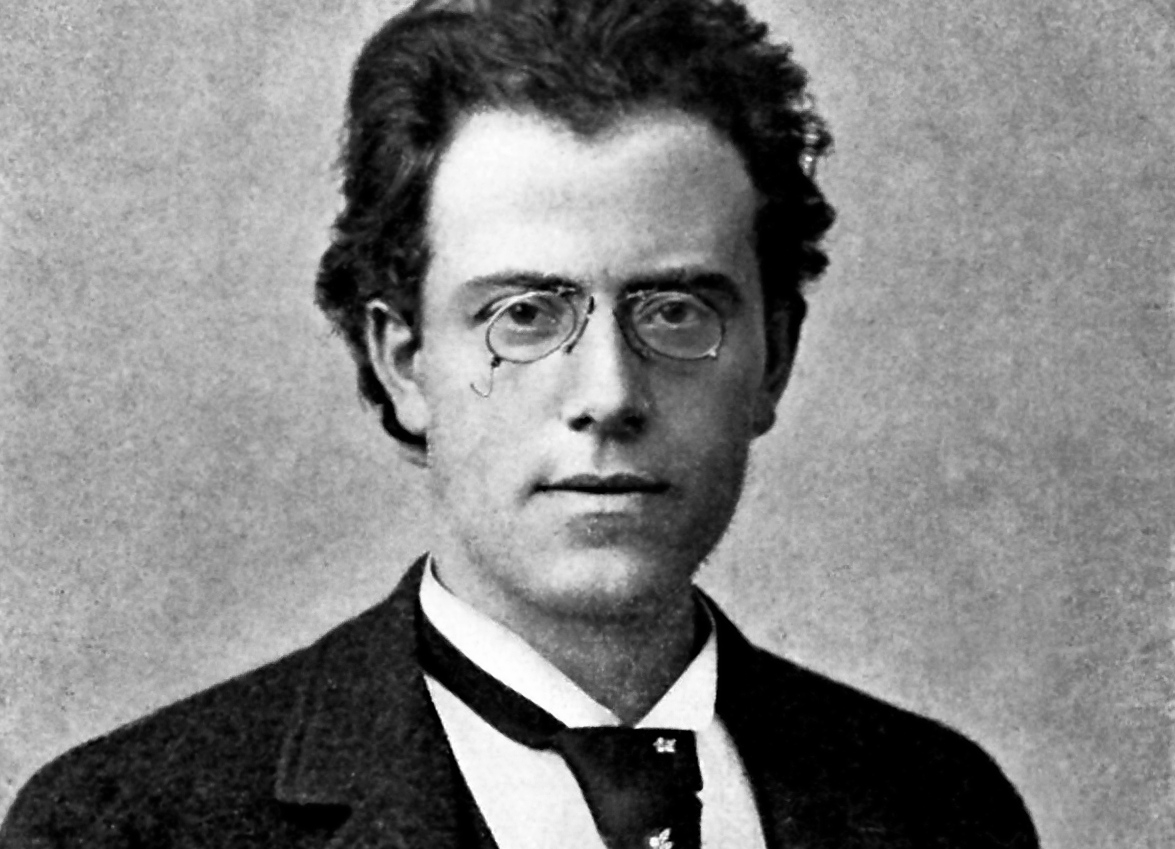

In Gustav Mahler’s body of work, the composer suggests his compositions are more than just music, and that’s part of the attraction. As if all those references to folk music, to nature sounds, the constantly recurring funeral marches, and the ambiguously waltzing Ländlers tell us something beyond the music. Mahler sought to capture his life experiences in exemplary, biographical and confessional music. He did so with a level of musical abstraction that aligns with the instincts and reflexes anchored in human psychology as recognized by Sigmund Freud, who happened to live around the corner from Mahler in fin de siècle Vienna.

Mahler took inspiration from texts or literary and philosophical ideas; music enabled him to voice the ‘hidden treasure’ beyond the words. In Mahler’s eyes, that hidden treasure was either the irrational wonder of life or those gruesome, incomprehensible aspects of human existence that cannot be expressed in words. Mahler was profoundly stirred by life’s contradictions.

In Gustav Mahler’s body of work, the composer suggests his compositions are more than just music, and that’s part of the attraction. As if all those references to folk music, to nature sounds, the constantly recurring funeral marches, and the ambiguously waltzing Ländlers tell us something beyond the music. Mahler sought to capture his life experiences in exemplary, biographical and confessional music. He did so with a level of musical abstraction that aligns with the instincts and reflexes anchored in human psychology as recognized by Sigmund Freud, who happened to live around the corner from Mahler in fin de siècle Vienna.

Mahler took inspiration from texts or literary and philosophical ideas; music enabled him to voice the ‘hidden treasure’ beyond the words. In Mahler’s eyes, that hidden treasure was either the irrational wonder of life or those gruesome, incomprehensible aspects of human existence that cannot be expressed in words. Mahler was profoundly stirred by life’s contradictions.

Mahler’s songs offer the best opportunity for reconstructing his life experience, in as far as that is possible. Until he was about forty, Mahler drew from Des Knaben Wunderhorn, a collection of German folkloric poetry dating from 1808. These texts revolve around nature, the romantic German woodlands, lost loves and soldiers destined never to return home, as well as a naive sense of connection with something eternal, something Mahler dearly hoped existed. Additionally, these texts share some common ground with the dark side of the historical fairy tales as chronicled by the Brothers Grimm. This fits well with Mahler’s music, which can shift from macabre and grim to the sarcastic irony that was no stranger to his daily life.

Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen

In 1883, Mahler was inspired by the Wunderhorn collection to write his own texts for Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, songs about a romantic wayfarer who might have stepped off the pages of Schubert’s Winterreise. The poem’s first line sets the scene: a young man sits sadly in a darkened room while his sweetheart is getting married. The piano – or, in the orchestral version, the woodwinds – opens with a combination of an ornamental turn and a leaping fourth, a bird call that refers to the woodland journey the dejected lover is about to undertake.

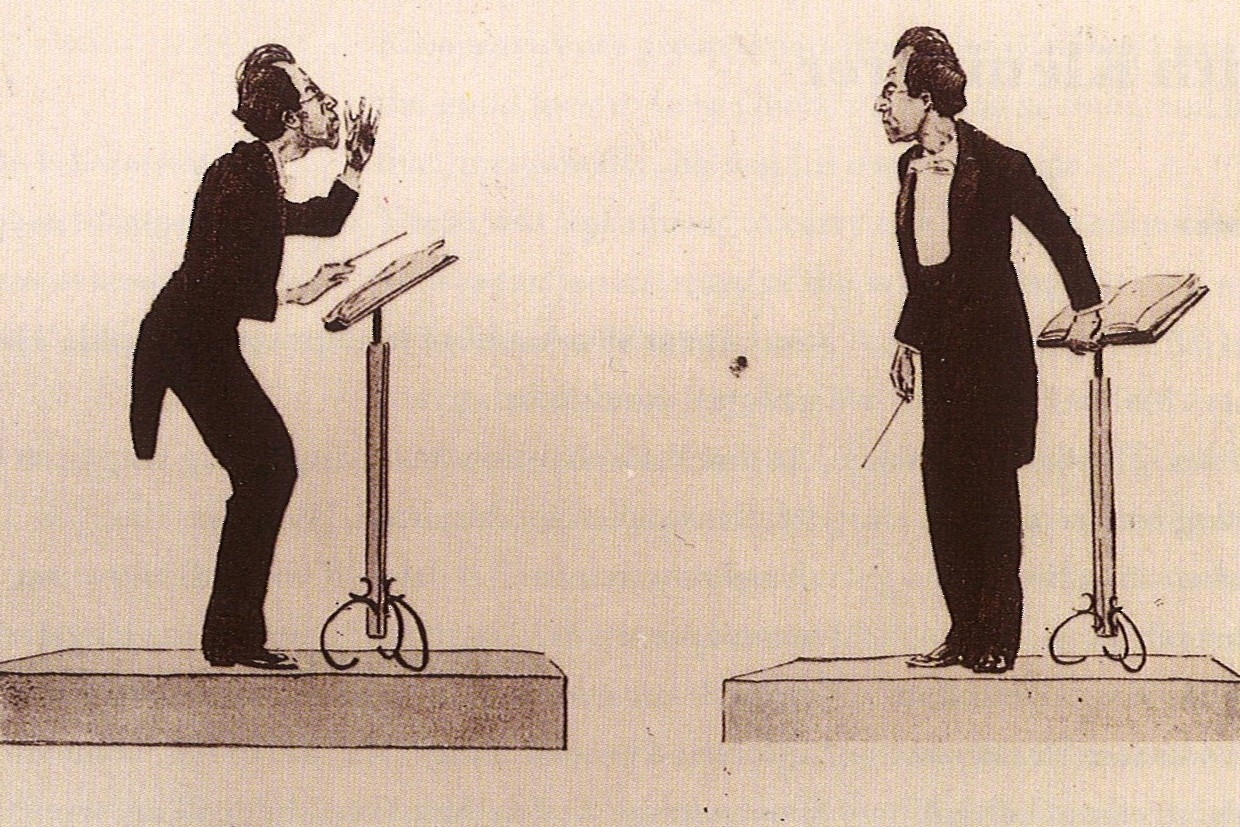

Illustration: Olivia Ettema

The generously unfolding melody in Ging heut morgen übers Feld already displays Mahler’s signature combination of carefree folk music and light-footed exuberance – critics even accused Mahler of a penchant for the banal. Depending on the context, this might represent either a lust for life or an attempt to escape it, as in a drunken stupor. But Mahler often used the same musical gesture to convey opposing meanings, and ambiguity is far from banal.

The song cycle ends with a nocturnal funeral march – one of many written by Mahler. The grieving young man pauses at a Linden tree, which also symbolizes the peacefulness of death in Schubert’s music. Winterreise, however, ends with a grim final encounter with death: a ‘wunderlicher Alter’, a remarkable older person repeating the same dreary tune on his hurdy-gurdy, despite his frozen fingers. But Mahler’s ‘Wayfarer’ seems to transcend death, and he returns to nature, the origin of all things. In the final measures, however, the bubble bursts and the song shifts into a minor key, a poignant reminder of the funeral march. Twenty-five years later, in the last song of Mahler’s final vocal work, Das Lied von der Erde (1908-09), this leaning towards the transcendent reappears, although without shifting to the minor key.

Des Knaben Wunderhorn

Mahler’s sense of irony and his fondness for grotesque ambiguity are vividly apparent in such Wunderhorn songs as Lob des hohen Verstandes (1896) or Ablösung im Sommer (1887). In Lob des hohen Verstandes, a donkey must judge a singing contest between a cuckoo and a nightingale. The nightingale takes second place to the cuckoo, who can’t even sing. Mahler’s music is lightly ironic, repeating surly imitations of the two birds and the donkey. The song has the good-natured simplicity of a child’s parable. Mahler seems to be referring to the music critics when he says that the best can’t win when a donkey is the judge.

The best can’t win when a donkey is the judge

Ablösung im Sommer may seem momentarily cheerful, but it is much darker and characteristically ambivalent. It starts with the wrenchingly cheerful announcement that the cuckoo has died. In fact, listeners can almost hear the bird falling comically off its perch. But then, who will sing in summer? The sunny answer arrives in A major: the nightingale! This changing of the guard is ruthlessly represented in both the lyrics and the sudden shift to a major key; it’s as unflinching as an evil fairy tale. In this context, the guilelessly naive cuckoo’s call – heard between two extremes – has a decidedly grotesque ring. The instrumental imitation is ominously shrill – like a taunting nursery song. Mahler wrote the words ‘Mit Humor’ above this song’s title...

The Wunderhorn songs also convey hope and joy, although many are coloured by a melancholic awareness of death, including Wo die schönen Trompeten blasen (1898). The marches seem to suggest a final macabre surrender, as in Der Tambourg’sell (1901). In Mahler’s later music, the sense of hope would remain, albeit increasingly sublimated, although the joie de vivre sometimes lost its sheen.

Rückert-Lieder

Circa 1900, after twenty years of working with the Wunderhorn texts, Mahler turned to the poetry of Friedrich Rückert (1788-1866), whose lyrically romantic oeuvre corresponded with Mahler’s preoccupation with existential thought. Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen, from the first Rückert-Lieder song cycle (1901-02), is just one example of that understated mood. A darkly supplicating English horn suggests lonely reflections on a lost love; this lament in a minor key also paradoxically presages Mahler’s ultimate love song, the famous Adagietto from the Fifth Symphony. The words of Rückert’s poem, when translated to the key of C minor, sound like a detached, melancholic version of Mahler’s declaration of death-transcending love for his wife Alma. Although Mahler composed the Adagietto shortly after completing this Rückert setting, no one knows for sure if he also made the connection cited above. However, the combination of melancholy and all-encompassing love remains a recurring theme within Mahler’s work.

Another typical paradox is Mahler’s decision, after setting the first Rückert-Lieder, to turn to the intensely heartrending Kindertotenlieder (1901-05). The choice had no link whatsoever with Mahler’s happiness during that sunny period of his life. He had been married to Alma for less than a year, was a successful artistic director and chief conductor of the Vienna State Opera and had just had a villa built on Lake Wörtherncluding ‘Seeblick’, his combination boat house and composer’s hut – where he spent his summers composing music.

Anecdotes from that time reveal a happy man, living life to its fullest; one who swam many kilometres in Lake Wörther and enjoyed lengthy hikes in the mountains. In short, a driven man who told conductor Bruno Walter, his friend and associate, that he had already ‘composed’ all those mountains. Of course, an image of an egocentric artist with eccentric quirks also emerges; maybe that’s inevitable when your life forms the departure point for your artistic creations. It’s said that Mahler could become so distracted during conversation that he would stir his coffee with a cigarette, take a sip and, thinking he had just inhaled, expel the vaporized coffee into the face of his interlocutor.

It wasn’t until 1907 – four years before his death – that misfortune struck Mahler. In the summer of that year, Mahler’s four-year-old daughter Maria Anna died, and he was diagnosed with a life-threatening heart condition. An estrangement from Alma followed and, eventually, profound despair about her subsequent adultery. Mahler composed hisKindertotenlieder before his daughter’s death, a coincidence that spookily coincides with his leaning towards the macabre and his wrestling with life’s happenstance. What’s even more ominous is that Maria Anna died from the same disease – diphtheria – that overcame Rückert’s two young children in 1833. In fact, before the traumatized poet died in 1872, he had written more than four hundred Kindertotenlieder, which he refused to publish during his lifetime. Yet for Mahler, there was nothing autobiographical about the Kindertotenlieder. Instead, empathy is the pent-up emotion he composed into the work, crystallized into sublime, grandiose music.

Nobody knows why Mahler wrote such intensely sorrowful, transcendental songs during the happiest years of his life. Similarly, there is no explanation for his jet-black Sixth Symphony, composed immediately after the Kindertotenliederand before tragedy struck.

Das Lied von der Erde

Das Lied von der Erde, written one year after that fateful summer of 1907, is another existential work, but less emotionally charged and smothered with sorrow than the works created before adversity struck. In Das Trinklied vom Jammer der Erde, which opens this grand combination of symphony and song cycle, the regret – or Jammer – dissolves in the poet’s drunkenness, and he celebrates life again, if only because the music is so powerful. In the last movement, Der Abschied, Benjamin Britten heard nothing but transcendental musical beauty, although he found it cruel. ‘It has the beauty of loneliness, & of pain: of strength & freedom,’ wrote the British composer to his friend Henry Boys ‘The beauty of disappointment & never-satisfied love. The cruel beauty of nature, and the everlasting beauty of monotony.’ With the exception of strength and freedom, everything Benjamin Britten links to the concept of beauty is related to pain. Perhaps that brings us closer to Mahler’s little-understood moods and innermost emotions.

Those who listen to the music on its own can hear this disintegration in the unregulated freedom that departs from the measured rhythm. Mahler spun a complex fabric of melodic threads derived from one another, and their rhythm floated so freely he wondered if the piece could even be conducted. Towards the end, Der Abschied flows almost unchanneled, dying out in stillness. In this weightless context, the singer’s softly repeated, elongated ‘Ewig’ – eternal – can mean anything. Benjamin Britten heard never-ending music. ‘…it goes on forever, even if it is never performed again – that final chord is printed on the atmosphere.’

Mahler’s songs offer the best opportunity for reconstructing his life experience, in as far as that is possible. Until he was about forty, Mahler drew from Des Knaben Wunderhorn, a collection of German folkloric poetry dating from 1808. These texts revolve around nature, the romantic German woodlands, lost loves and soldiers destined never to return home, as well as a naive sense of connection with something eternal, something Mahler dearly hoped existed. Additionally, these texts share some common ground with the dark side of the historical fairy tales as chronicled by the Brothers Grimm. This fits well with Mahler’s music, which can shift from macabre and grim to the sarcastic irony that was no stranger to his daily life.

Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen

In 1883, Mahler was inspired by the Wunderhorn collection to write his own texts for Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, songs about a romantic wayfarer who might have stepped off the pages of Schubert’s Winterreise. The poem’s first line sets the scene: a young man sits sadly in a darkened room while his sweetheart is getting married. The piano – or, in the orchestral version, the woodwinds – opens with a combination of an ornamental turn and a leaping fourth, a bird call that refers to the woodland journey the dejected lover is about to undertake.

Illustration: Olivia Ettema

The generously unfolding melody in Ging heut morgen übers Feld already displays Mahler’s signature combination of carefree folk music and light-footed exuberance – critics even accused Mahler of a penchant for the banal. Depending on the context, this might represent either a lust for life or an attempt to escape it, as in a drunken stupor. But Mahler often used the same musical gesture to convey opposing meanings, and ambiguity is far from banal.

The song cycle ends with a nocturnal funeral march – one of many written by Mahler. The grieving young man pauses at a Linden tree, which also symbolizes the peacefulness of death in Schubert’s music. Winterreise, however, ends with a grim final encounter with death: a ‘wunderlicher Alter’, a remarkable older person repeating the same dreary tune on his hurdy-gurdy, despite his frozen fingers. But Mahler’s ‘Wayfarer’ seems to transcend death, and he returns to nature, the origin of all things. In the final measures, however, the bubble bursts and the song shifts into a minor key, a poignant reminder of the funeral march. Twenty-five years later, in the last song of Mahler’s final vocal work, Das Lied von der Erde (1908-09), this leaning towards the transcendent reappears, although without shifting to the minor key.

Des Knaben Wunderhorn

Mahler’s sense of irony and his fondness for grotesque ambiguity are vividly apparent in such Wunderhorn songs as Lob des hohen Verstandes (1896) or Ablösung im Sommer (1887). In Lob des hohen Verstandes, a donkey must judge a singing contest between a cuckoo and a nightingale. The nightingale takes second place to the cuckoo, who can’t even sing. Mahler’s music is lightly ironic, repeating surly imitations of the two birds and the donkey. The song has the good-natured simplicity of a child’s parable. Mahler seems to be referring to the music critics when he says that the best can’t win when a donkey is the judge.

The best can’t win when a donkey is the judge

Ablösung im Sommer may seem momentarily cheerful, but it is much darker and characteristically ambivalent. It starts with the wrenchingly cheerful announcement that the cuckoo has died. In fact, listeners can almost hear the bird falling comically off its perch. But then, who will sing in summer? The sunny answer arrives in A major: the nightingale! This changing of the guard is ruthlessly represented in both the lyrics and the sudden shift to a major key; it’s as unflinching as an evil fairy tale. In this context, the guilelessly naive cuckoo’s call – heard between two extremes – has a decidedly grotesque ring. The instrumental imitation is ominously shrill – like a taunting nursery song. Mahler wrote the words ‘Mit Humor’ above this song’s title...

The Wunderhorn songs also convey hope and joy, although many are coloured by a melancholic awareness of death, including Wo die schönen Trompeten blasen (1898). The marches seem to suggest a final macabre surrender, as in Der Tambourg’sell (1901). In Mahler’s later music, the sense of hope would remain, albeit increasingly sublimated, although the joie de vivre sometimes lost its sheen.

Rückert-Lieder

Circa 1900, after twenty years of working with the Wunderhorn texts, Mahler turned to the poetry of Friedrich Rückert (1788-1866), whose lyrically romantic oeuvre corresponded with Mahler’s preoccupation with existential thought. Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen, from the first Rückert-Lieder song cycle (1901-02), is just one example of that understated mood. A darkly supplicating English horn suggests lonely reflections on a lost love; this lament in a minor key also paradoxically presages Mahler’s ultimate love song, the famous Adagietto from the Fifth Symphony. The words of Rückert’s poem, when translated to the key of C minor, sound like a detached, melancholic version of Mahler’s declaration of death-transcending love for his wife Alma. Although Mahler composed the Adagietto shortly after completing this Rückert setting, no one knows for sure if he also made the connection cited above. However, the combination of melancholy and all-encompassing love remains a recurring theme within Mahler’s work.

Another typical paradox is Mahler’s decision, after setting the first Rückert-Lieder, to turn to the intensely heartrending Kindertotenlieder (1901-05). The choice had no link whatsoever with Mahler’s happiness during that sunny period of his life. He had been married to Alma for less than a year, was a successful artistic director and chief conductor of the Vienna State Opera and had just had a villa built on Lake Wörtherncluding ‘Seeblick’, his combination boat house and composer’s hut – where he spent his summers composing music.

Anecdotes from that time reveal a happy man, living life to its fullest; one who swam many kilometres in Lake Wörther and enjoyed lengthy hikes in the mountains. In short, a driven man who told conductor Bruno Walter, his friend and associate, that he had already ‘composed’ all those mountains. Of course, an image of an egocentric artist with eccentric quirks also emerges; maybe that’s inevitable when your life forms the departure point for your artistic creations. It’s said that Mahler could become so distracted during conversation that he would stir his coffee with a cigarette, take a sip and, thinking he had just inhaled, expel the vaporized coffee into the face of his interlocutor.

It wasn’t until 1907 – four years before his death – that misfortune struck Mahler. In the summer of that year, Mahler’s four-year-old daughter Maria Anna died, and he was diagnosed with a life-threatening heart condition. An estrangement from Alma followed and, eventually, profound despair about her subsequent adultery. Mahler composed hisKindertotenlieder before his daughter’s death, a coincidence that spookily coincides with his leaning towards the macabre and his wrestling with life’s happenstance. What’s even more ominous is that Maria Anna died from the same disease – diphtheria – that overcame Rückert’s two young children in 1833. In fact, before the traumatized poet died in 1872, he had written more than four hundred Kindertotenlieder, which he refused to publish during his lifetime. Yet for Mahler, there was nothing autobiographical about the Kindertotenlieder. Instead, empathy is the pent-up emotion he composed into the work, crystallized into sublime, grandiose music.

Nobody knows why Mahler wrote such intensely sorrowful, transcendental songs during the happiest years of his life. Similarly, there is no explanation for his jet-black Sixth Symphony, composed immediately after the Kindertotenliederand before tragedy struck.

Das Lied von der Erde

Das Lied von der Erde, written one year after that fateful summer of 1907, is another existential work, but less emotionally charged and smothered with sorrow than the works created before adversity struck. In Das Trinklied vom Jammer der Erde, which opens this grand combination of symphony and song cycle, the regret – or Jammer – dissolves in the poet’s drunkenness, and he celebrates life again, if only because the music is so powerful. In the last movement, Der Abschied, Benjamin Britten heard nothing but transcendental musical beauty, although he found it cruel. ‘It has the beauty of loneliness, & of pain: of strength & freedom,’ wrote the British composer to his friend Henry Boys ‘The beauty of disappointment & never-satisfied love. The cruel beauty of nature, and the everlasting beauty of monotony.’ With the exception of strength and freedom, everything Benjamin Britten links to the concept of beauty is related to pain. Perhaps that brings us closer to Mahler’s little-understood moods and innermost emotions.

Those who listen to the music on its own can hear this disintegration in the unregulated freedom that departs from the measured rhythm. Mahler spun a complex fabric of melodic threads derived from one another, and their rhythm floated so freely he wondered if the piece could even be conducted. Towards the end, Der Abschied flows almost unchanneled, dying out in stillness. In this weightless context, the singer’s softly repeated, elongated ‘Ewig’ – eternal – can mean anything. Benjamin Britten heard never-ending music. ‘…it goes on forever, even if it is never performed again – that final chord is printed on the atmosphere.’