Mahler Festival: Kirill Petrenko and the Berliner Philharmoniker in Mahler's Symphony No. 9 (English)

Main Hall 17 mei 2025 20.15 uur

Berliner Philharmoniker

Kirill Petrenko conductor

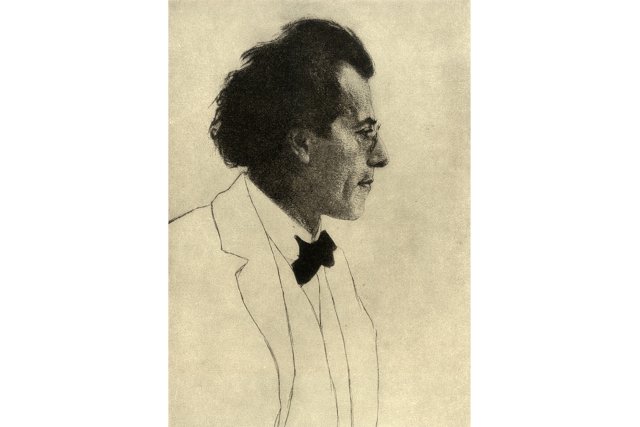

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Symphony No. 9 in D major (1908-09)

Andante comodo

Im Tempo eines gemächlichen Ländlers: etwas täppisch und sehr derb

Rondo–Burleske. Allegro assai. Sehr trotzig

Adagio. Sehr langsam und noch zurückhaltend

no interval

end ± 9.40PM

Berliner Philharmoniker

Kirill Petrenko conductor

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Symphony No. 9 in D major (1908-09)

Andante comodo

Im Tempo eines gemächlichen Ländlers: etwas täppisch und sehr derb

Rondo–Burleske. Allegro assai. Sehr trotzig

Adagio. Sehr langsam und noch zurückhaltend

no interval

end ± 9.40PM

Toelichting

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Symphony No. 9

On 26 June 1912, Bruno Walter conducted the Vienna Philharmonic in the first performance of Gustav Mahler’s Ninth Symphony in D major. The composer, however, did not attend the premiere, because he had died the previous year, knowing full well that his Ninth Symphony would be the last major symphonic work he would ever complete. With that, the uneasy composer’s worst fears became a reality. Because, like Ludwig van Beethoven, Franz Schubert and Anton Bruckner before him, the ninth symphony represented the end of the line. After completing his Eighth Symphony, Mahler had tried to outwit fate by composing a ‘song-symphony,’ Das Lied von der Erde, instead of writing a new, or ‘ninth,’ symphony. But once he’d set his ‘ninth’ symphony to paper, he was free to start on symphony number ten. Sadly, Mahler didn’t have enough time to complete that final work. The Tenth Symphony’s opening Adagio was nearly finished, but only a few sketches of the other movements were complete when Mahler died on 18 May 1911.

Mahler wrote his Ninth Symphony in 1908-09. As usual, he spent the summer in his composer’s hut in Toblach. While his previous symphonies had often taken two years to write, he was almost finished with this new work by August, despite initial disruptions from noisy neighbours and a barking dog. Later that month, he proudly described the work as ‘a nice addition to my little family. It’s something that’s been on the tip of my tongue for a long time; the work (as a whole) is perhaps most like the Fourth (yet quite different).’ And indeed, in some ways, the Ninth, like the Fourth, is built around a quasi-chamber music-like concept, yet it’s very different. In the Ninth, Mahler steps away, at least in part, from the established symphonic traditions. For example, the symphony’s overall structure is striking: the outer movements are slow, while the middle movements are faster, leading some analysts to see parallels with Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony, “Pathétique”, from 1893.

Mahler’s Ninth Symphony contains fewer sweeping melodic phrases than his previous works. Instead, Mahler employs shorter motifs and fragments on which he seems to improvise. And although remnants of the nineteenth century are clearly audible, the doors to the twentieth century have been flung open. During an era when composers such as Igor Stravinsky and Béla Bartók were making a name for themselves, Mahler also wrote – in the words of philosopher musician Theodor Adorno (1903-1969) – ‘the first example of new music’. Arnold Schönberg, one of the new crop of revolutionary composers, described his experiences with the symphony as follows: ‘Mahler’s Ninth is most strange. In it, the author hardly speaks as an individual any longer. It almost seems like this work must have a concealed author who used Mahler merely as his spokesman, as his mouthpiece. This symphony is no longer couched in the personal tone. It consists, so to speak, of objective, almost passionless statements of beauty which become perceptible only to one who can dispense with animal warmth and feels at home in spiritual coolness.’

Mahler uses his Ninth Symphony not only as a farewell to a musical past but also as a farewell to life. ‘A farewell to everyone he loved and to the world. And to his art, life, and music,’ wrote Willem Mengelberg, Mahler’s friend and conductor of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra between 1895 and 1945. Or, as Mahler wrote in his manuscript of the score, ‘O Jugendzeit! Entschundene! O Liebe! Verwehte!’ (O Youth! Vanished! O Love! Blown away!) During the final years of his life, the composer faced many challenges. In 1907, his four-year-old daughter Maria had died, he’d been diagnosed with a heart condition, he lost his job at the Vienna State Opera, and his relationship with his beloved Alma had cooled. Mahler’s preoccupation with parting and death had already surfaced in his recently completed Das Lied von der Erde. The Ninth was intended as a sort of follow-up: the descending second with which the alto sings of eternal life in ‘Der Abschied’ – the last movement of Das Lied von der Erde – is echoed in the first movement of the Ninth. References to a theme from Beethoven’s Sonata No. 26, known as ‘Les Adieux’ (The Farewell), can hardly be coincidental. And could the hesitant rhythm in the opening movement represent Mahler’s irregular heartbeat?

On 26 June 1912, Bruno Walter conducted the Vienna Philharmonic in the first performance of Gustav Mahler’s Ninth Symphony in D major. The composer, however, did not attend the premiere, because he had died the previous year, knowing full well that his Ninth Symphony would be the last major symphonic work he would ever complete. With that, the uneasy composer’s worst fears became a reality. Because, like Ludwig van Beethoven, Franz Schubert and Anton Bruckner before him, the ninth symphony represented the end of the line. After completing his Eighth Symphony, Mahler had tried to outwit fate by composing a ‘song-symphony,’ Das Lied von der Erde, instead of writing a new, or ‘ninth,’ symphony. But once he’d set his ‘ninth’ symphony to paper, he was free to start on symphony number ten. Sadly, Mahler didn’t have enough time to complete that final work. The Tenth Symphony’s opening Adagio was nearly finished, but only a few sketches of the other movements were complete when Mahler died on 18 May 1911.

Mahler wrote his Ninth Symphony in 1908-09. As usual, he spent the summer in his composer’s hut in Toblach. While his previous symphonies had often taken two years to write, he was almost finished with this new work by August, despite initial disruptions from noisy neighbours and a barking dog. Later that month, he proudly described the work as ‘a nice addition to my little family. It’s something that’s been on the tip of my tongue for a long time; the work (as a whole) is perhaps most like the Fourth (yet quite different).’ And indeed, in some ways, the Ninth, like the Fourth, is built around a quasi-chamber music-like concept, yet it’s very different. In the Ninth, Mahler steps away, at least in part, from the established symphonic traditions. For example, the symphony’s overall structure is striking: the outer movements are slow, while the middle movements are faster, leading some analysts to see parallels with Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony, “Pathétique”, from 1893.

Mahler’s Ninth Symphony contains fewer sweeping melodic phrases than his previous works. Instead, Mahler employs shorter motifs and fragments on which he seems to improvise. And although remnants of the nineteenth century are clearly audible, the doors to the twentieth century have been flung open. During an era when composers such as Igor Stravinsky and Béla Bartók were making a name for themselves, Mahler also wrote – in the words of philosopher musician Theodor Adorno (1903-1969) – ‘the first example of new music’. Arnold Schönberg, one of the new crop of revolutionary composers, described his experiences with the symphony as follows: ‘Mahler’s Ninth is most strange. In it, the author hardly speaks as an individual any longer. It almost seems like this work must have a concealed author who used Mahler merely as his spokesman, as his mouthpiece. This symphony is no longer couched in the personal tone. It consists, so to speak, of objective, almost passionless statements of beauty which become perceptible only to one who can dispense with animal warmth and feels at home in spiritual coolness.’

Mahler uses his Ninth Symphony not only as a farewell to a musical past but also as a farewell to life. ‘A farewell to everyone he loved and to the world. And to his art, life, and music,’ wrote Willem Mengelberg, Mahler’s friend and conductor of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra between 1895 and 1945. Or, as Mahler wrote in his manuscript of the score, ‘O Jugendzeit! Entschundene! O Liebe! Verwehte!’ (O Youth! Vanished! O Love! Blown away!) During the final years of his life, the composer faced many challenges. In 1907, his four-year-old daughter Maria had died, he’d been diagnosed with a heart condition, he lost his job at the Vienna State Opera, and his relationship with his beloved Alma had cooled. Mahler’s preoccupation with parting and death had already surfaced in his recently completed Das Lied von der Erde. The Ninth was intended as a sort of follow-up: the descending second with which the alto sings of eternal life in ‘Der Abschied’ – the last movement of Das Lied von der Erde – is echoed in the first movement of the Ninth. References to a theme from Beethoven’s Sonata No. 26, known as ‘Les Adieux’ (The Farewell), can hardly be coincidental. And could the hesitant rhythm in the opening movement represent Mahler’s irregular heartbeat?

‘The first movement is the most glorious he ever wrote,’ said composer Alban Berg, a contemporary of Mahler’s. ‘It expresses an extraordinary love of the earth, for Nature. The longing to live on it in peace, to enjoy it completely, to the very heart of one’s being, before death comes, as irresistibly it does.’ Berg thought the entire movement was permeated by traces of an approaching end. The opening movement is loosely based on the traditional sonata form but is also sometimes described as ‘variation form’. Some musicologists view Mahler’s treatment of the material as a forerunner of the working methods of the serialists from the Second Viennese School. Polyphony and linear thinking play a crucial role. In addition, the first movement is characterized by dramatic shifts in dynamics and mood, ranging from tender sonorities to threatening eruptions, despair and wonder. A massive climax leads to a funeral march like a ‘profound funeral procession’.

According to composer Dieter Schnebel, the second movement is made up of ‘composed ruins.’ There is a Ländler and a waltz, which Mahler encases in stark and grotesque humour. Is this a dance macabre, in which the devil plays the violin? The third and

following movement (dedicated to ‘My brothers in Apollo’) is also characterized by pitch-black sarcasm. The Scherzo presents mocking themes and unfolds in fugue-like passages. Mahler expert Deryck Cooke (1919-1976) described this movement as devised chaos... a bright burst of hellish laughter about the futility of everything; Willem Mengelberg was struck by this movement’s ‘gallows humour’.

The fourth and final movement is a broadly painted Adagio, not in D major but in D-flat major. Cooke wrote about the painful sadness of the finale, following all the horrors and hopelessness of the first three movements, and the way Mahler’s ineradicable love of life is still visible; this shows how truly great music can simultaneously express different, opposing emotions. According to Cooke, this symphony is the musical equivalent of what the poet Rilke called ‘dennoch preisen’ – praising life in spite of everything. Shortly before the symphony’s end, the composer quotes a passage from one of his Kindertotenlieder (1901-04): ‘The day is fine on yonder heights.’ As if he’s already stepped beyond this world. Above the final measures, in which the closing notes die out, Mahler wrote, ‘O Schönheit! Liebe! Leb wol! Leb wol.’ (Oh beauty, Love! Live well! Live well.)

‘The first movement is the most glorious he ever wrote,’ said composer Alban Berg, a contemporary of Mahler’s. ‘It expresses an extraordinary love of the earth, for Nature. The longing to live on it in peace, to enjoy it completely, to the very heart of one’s being, before death comes, as irresistibly it does.’ Berg thought the entire movement was permeated by traces of an approaching end. The opening movement is loosely based on the traditional sonata form but is also sometimes described as ‘variation form’. Some musicologists view Mahler’s treatment of the material as a forerunner of the working methods of the serialists from the Second Viennese School. Polyphony and linear thinking play a crucial role. In addition, the first movement is characterized by dramatic shifts in dynamics and mood, ranging from tender sonorities to threatening eruptions, despair and wonder. A massive climax leads to a funeral march like a ‘profound funeral procession’.

According to composer Dieter Schnebel, the second movement is made up of ‘composed ruins.’ There is a Ländler and a waltz, which Mahler encases in stark and grotesque humour. Is this a dance macabre, in which the devil plays the violin? The third and

following movement (dedicated to ‘My brothers in Apollo’) is also characterized by pitch-black sarcasm. The Scherzo presents mocking themes and unfolds in fugue-like passages. Mahler expert Deryck Cooke (1919-1976) described this movement as devised chaos... a bright burst of hellish laughter about the futility of everything; Willem Mengelberg was struck by this movement’s ‘gallows humour’.

The fourth and final movement is a broadly painted Adagio, not in D major but in D-flat major. Cooke wrote about the painful sadness of the finale, following all the horrors and hopelessness of the first three movements, and the way Mahler’s ineradicable love of life is still visible; this shows how truly great music can simultaneously express different, opposing emotions. According to Cooke, this symphony is the musical equivalent of what the poet Rilke called ‘dennoch preisen’ – praising life in spite of everything. Shortly before the symphony’s end, the composer quotes a passage from one of his Kindertotenlieder (1901-04): ‘The day is fine on yonder heights.’ As if he’s already stepped beyond this world. Above the final measures, in which the closing notes die out, Mahler wrote, ‘O Schönheit! Liebe! Leb wol! Leb wol.’ (Oh beauty, Love! Live well! Live well.)

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Symphony No. 9

On 26 June 1912, Bruno Walter conducted the Vienna Philharmonic in the first performance of Gustav Mahler’s Ninth Symphony in D major. The composer, however, did not attend the premiere, because he had died the previous year, knowing full well that his Ninth Symphony would be the last major symphonic work he would ever complete. With that, the uneasy composer’s worst fears became a reality. Because, like Ludwig van Beethoven, Franz Schubert and Anton Bruckner before him, the ninth symphony represented the end of the line. After completing his Eighth Symphony, Mahler had tried to outwit fate by composing a ‘song-symphony,’ Das Lied von der Erde, instead of writing a new, or ‘ninth,’ symphony. But once he’d set his ‘ninth’ symphony to paper, he was free to start on symphony number ten. Sadly, Mahler didn’t have enough time to complete that final work. The Tenth Symphony’s opening Adagio was nearly finished, but only a few sketches of the other movements were complete when Mahler died on 18 May 1911.

Mahler wrote his Ninth Symphony in 1908-09. As usual, he spent the summer in his composer’s hut in Toblach. While his previous symphonies had often taken two years to write, he was almost finished with this new work by August, despite initial disruptions from noisy neighbours and a barking dog. Later that month, he proudly described the work as ‘a nice addition to my little family. It’s something that’s been on the tip of my tongue for a long time; the work (as a whole) is perhaps most like the Fourth (yet quite different).’ And indeed, in some ways, the Ninth, like the Fourth, is built around a quasi-chamber music-like concept, yet it’s very different. In the Ninth, Mahler steps away, at least in part, from the established symphonic traditions. For example, the symphony’s overall structure is striking: the outer movements are slow, while the middle movements are faster, leading some analysts to see parallels with Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony, “Pathétique”, from 1893.

Mahler’s Ninth Symphony contains fewer sweeping melodic phrases than his previous works. Instead, Mahler employs shorter motifs and fragments on which he seems to improvise. And although remnants of the nineteenth century are clearly audible, the doors to the twentieth century have been flung open. During an era when composers such as Igor Stravinsky and Béla Bartók were making a name for themselves, Mahler also wrote – in the words of philosopher musician Theodor Adorno (1903-1969) – ‘the first example of new music’. Arnold Schönberg, one of the new crop of revolutionary composers, described his experiences with the symphony as follows: ‘Mahler’s Ninth is most strange. In it, the author hardly speaks as an individual any longer. It almost seems like this work must have a concealed author who used Mahler merely as his spokesman, as his mouthpiece. This symphony is no longer couched in the personal tone. It consists, so to speak, of objective, almost passionless statements of beauty which become perceptible only to one who can dispense with animal warmth and feels at home in spiritual coolness.’

Mahler uses his Ninth Symphony not only as a farewell to a musical past but also as a farewell to life. ‘A farewell to everyone he loved and to the world. And to his art, life, and music,’ wrote Willem Mengelberg, Mahler’s friend and conductor of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra between 1895 and 1945. Or, as Mahler wrote in his manuscript of the score, ‘O Jugendzeit! Entschundene! O Liebe! Verwehte!’ (O Youth! Vanished! O Love! Blown away!) During the final years of his life, the composer faced many challenges. In 1907, his four-year-old daughter Maria had died, he’d been diagnosed with a heart condition, he lost his job at the Vienna State Opera, and his relationship with his beloved Alma had cooled. Mahler’s preoccupation with parting and death had already surfaced in his recently completed Das Lied von der Erde. The Ninth was intended as a sort of follow-up: the descending second with which the alto sings of eternal life in ‘Der Abschied’ – the last movement of Das Lied von der Erde – is echoed in the first movement of the Ninth. References to a theme from Beethoven’s Sonata No. 26, known as ‘Les Adieux’ (The Farewell), can hardly be coincidental. And could the hesitant rhythm in the opening movement represent Mahler’s irregular heartbeat?

On 26 June 1912, Bruno Walter conducted the Vienna Philharmonic in the first performance of Gustav Mahler’s Ninth Symphony in D major. The composer, however, did not attend the premiere, because he had died the previous year, knowing full well that his Ninth Symphony would be the last major symphonic work he would ever complete. With that, the uneasy composer’s worst fears became a reality. Because, like Ludwig van Beethoven, Franz Schubert and Anton Bruckner before him, the ninth symphony represented the end of the line. After completing his Eighth Symphony, Mahler had tried to outwit fate by composing a ‘song-symphony,’ Das Lied von der Erde, instead of writing a new, or ‘ninth,’ symphony. But once he’d set his ‘ninth’ symphony to paper, he was free to start on symphony number ten. Sadly, Mahler didn’t have enough time to complete that final work. The Tenth Symphony’s opening Adagio was nearly finished, but only a few sketches of the other movements were complete when Mahler died on 18 May 1911.

Mahler wrote his Ninth Symphony in 1908-09. As usual, he spent the summer in his composer’s hut in Toblach. While his previous symphonies had often taken two years to write, he was almost finished with this new work by August, despite initial disruptions from noisy neighbours and a barking dog. Later that month, he proudly described the work as ‘a nice addition to my little family. It’s something that’s been on the tip of my tongue for a long time; the work (as a whole) is perhaps most like the Fourth (yet quite different).’ And indeed, in some ways, the Ninth, like the Fourth, is built around a quasi-chamber music-like concept, yet it’s very different. In the Ninth, Mahler steps away, at least in part, from the established symphonic traditions. For example, the symphony’s overall structure is striking: the outer movements are slow, while the middle movements are faster, leading some analysts to see parallels with Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony, “Pathétique”, from 1893.

Mahler’s Ninth Symphony contains fewer sweeping melodic phrases than his previous works. Instead, Mahler employs shorter motifs and fragments on which he seems to improvise. And although remnants of the nineteenth century are clearly audible, the doors to the twentieth century have been flung open. During an era when composers such as Igor Stravinsky and Béla Bartók were making a name for themselves, Mahler also wrote – in the words of philosopher musician Theodor Adorno (1903-1969) – ‘the first example of new music’. Arnold Schönberg, one of the new crop of revolutionary composers, described his experiences with the symphony as follows: ‘Mahler’s Ninth is most strange. In it, the author hardly speaks as an individual any longer. It almost seems like this work must have a concealed author who used Mahler merely as his spokesman, as his mouthpiece. This symphony is no longer couched in the personal tone. It consists, so to speak, of objective, almost passionless statements of beauty which become perceptible only to one who can dispense with animal warmth and feels at home in spiritual coolness.’

Mahler uses his Ninth Symphony not only as a farewell to a musical past but also as a farewell to life. ‘A farewell to everyone he loved and to the world. And to his art, life, and music,’ wrote Willem Mengelberg, Mahler’s friend and conductor of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra between 1895 and 1945. Or, as Mahler wrote in his manuscript of the score, ‘O Jugendzeit! Entschundene! O Liebe! Verwehte!’ (O Youth! Vanished! O Love! Blown away!) During the final years of his life, the composer faced many challenges. In 1907, his four-year-old daughter Maria had died, he’d been diagnosed with a heart condition, he lost his job at the Vienna State Opera, and his relationship with his beloved Alma had cooled. Mahler’s preoccupation with parting and death had already surfaced in his recently completed Das Lied von der Erde. The Ninth was intended as a sort of follow-up: the descending second with which the alto sings of eternal life in ‘Der Abschied’ – the last movement of Das Lied von der Erde – is echoed in the first movement of the Ninth. References to a theme from Beethoven’s Sonata No. 26, known as ‘Les Adieux’ (The Farewell), can hardly be coincidental. And could the hesitant rhythm in the opening movement represent Mahler’s irregular heartbeat?

‘The first movement is the most glorious he ever wrote,’ said composer Alban Berg, a contemporary of Mahler’s. ‘It expresses an extraordinary love of the earth, for Nature. The longing to live on it in peace, to enjoy it completely, to the very heart of one’s being, before death comes, as irresistibly it does.’ Berg thought the entire movement was permeated by traces of an approaching end. The opening movement is loosely based on the traditional sonata form but is also sometimes described as ‘variation form’. Some musicologists view Mahler’s treatment of the material as a forerunner of the working methods of the serialists from the Second Viennese School. Polyphony and linear thinking play a crucial role. In addition, the first movement is characterized by dramatic shifts in dynamics and mood, ranging from tender sonorities to threatening eruptions, despair and wonder. A massive climax leads to a funeral march like a ‘profound funeral procession’.

According to composer Dieter Schnebel, the second movement is made up of ‘composed ruins.’ There is a Ländler and a waltz, which Mahler encases in stark and grotesque humour. Is this a dance macabre, in which the devil plays the violin? The third and

following movement (dedicated to ‘My brothers in Apollo’) is also characterized by pitch-black sarcasm. The Scherzo presents mocking themes and unfolds in fugue-like passages. Mahler expert Deryck Cooke (1919-1976) described this movement as devised chaos... a bright burst of hellish laughter about the futility of everything; Willem Mengelberg was struck by this movement’s ‘gallows humour’.

The fourth and final movement is a broadly painted Adagio, not in D major but in D-flat major. Cooke wrote about the painful sadness of the finale, following all the horrors and hopelessness of the first three movements, and the way Mahler’s ineradicable love of life is still visible; this shows how truly great music can simultaneously express different, opposing emotions. According to Cooke, this symphony is the musical equivalent of what the poet Rilke called ‘dennoch preisen’ – praising life in spite of everything. Shortly before the symphony’s end, the composer quotes a passage from one of his Kindertotenlieder (1901-04): ‘The day is fine on yonder heights.’ As if he’s already stepped beyond this world. Above the final measures, in which the closing notes die out, Mahler wrote, ‘O Schönheit! Liebe! Leb wol! Leb wol.’ (Oh beauty, Love! Live well! Live well.)

‘The first movement is the most glorious he ever wrote,’ said composer Alban Berg, a contemporary of Mahler’s. ‘It expresses an extraordinary love of the earth, for Nature. The longing to live on it in peace, to enjoy it completely, to the very heart of one’s being, before death comes, as irresistibly it does.’ Berg thought the entire movement was permeated by traces of an approaching end. The opening movement is loosely based on the traditional sonata form but is also sometimes described as ‘variation form’. Some musicologists view Mahler’s treatment of the material as a forerunner of the working methods of the serialists from the Second Viennese School. Polyphony and linear thinking play a crucial role. In addition, the first movement is characterized by dramatic shifts in dynamics and mood, ranging from tender sonorities to threatening eruptions, despair and wonder. A massive climax leads to a funeral march like a ‘profound funeral procession’.

According to composer Dieter Schnebel, the second movement is made up of ‘composed ruins.’ There is a Ländler and a waltz, which Mahler encases in stark and grotesque humour. Is this a dance macabre, in which the devil plays the violin? The third and

following movement (dedicated to ‘My brothers in Apollo’) is also characterized by pitch-black sarcasm. The Scherzo presents mocking themes and unfolds in fugue-like passages. Mahler expert Deryck Cooke (1919-1976) described this movement as devised chaos... a bright burst of hellish laughter about the futility of everything; Willem Mengelberg was struck by this movement’s ‘gallows humour’.

The fourth and final movement is a broadly painted Adagio, not in D major but in D-flat major. Cooke wrote about the painful sadness of the finale, following all the horrors and hopelessness of the first three movements, and the way Mahler’s ineradicable love of life is still visible; this shows how truly great music can simultaneously express different, opposing emotions. According to Cooke, this symphony is the musical equivalent of what the poet Rilke called ‘dennoch preisen’ – praising life in spite of everything. Shortly before the symphony’s end, the composer quotes a passage from one of his Kindertotenlieder (1901-04): ‘The day is fine on yonder heights.’ As if he’s already stepped beyond this world. Above the final measures, in which the closing notes die out, Mahler wrote, ‘O Schönheit! Liebe! Leb wol! Leb wol.’ (Oh beauty, Love! Live well! Live well.)

Biografie

Berliner Philharmoniker, orchestra

The Berliner Philharmoniker, founded in 1882, is one of the world’s leading symphony orchestras. Kirill Petrenko has been Chief Conductor since September 2019. Its first permanent conductor Hans von Bülow was followed by Arthur Nikisch (who introduced Mahler’s work to the orchestra), Wilhelm Furtwängler and Sergiu Celibidache.

Between 1895 and 1907, they played Mahler’s symphonies several times, conducted by Mahler. Their relationship with Herbert von Karajan (1955-1989) was highly productive, with many recordings and tours, as well as performances during the new Osterfestspiele in Salzburg. Claudio Abbado (1990-2002) added contemporary music, chamber music and concertante opera to the repertoire.

Sir Simon Rattle’s appointment in 2002 coincided with the start of an education programme, aimed at engaging broader and younger audiences – a focus that has also been central under Petrenko. Their Digital Concert Hall website was launched in 2009, and their own CD label Berliner Philharmoniker Recordings in 2014.

The Berliner Philharmoniker Foundation is supported by the State of Berlin and the German federal government, as well as by the generous participation of Deutsche Bank as its principal sponsor.

Kirill Petrenko, conductor

Kirill Petrenko has been Chief Conductor and Artistic Director of the Berliner Philharmoniker since the 2019-2020 season. Born in Omsk (Siberia), he received his training first in his home town and later in Austria. He established his conducting career in opera with positions at the Meininger Theater and the Komische Oper Berlin.

From 2013 to 2020, Petrenko was general Music Director of Bayerische Staatsoper. He has also made guest appearances at the world’s leading opera houses. Moreover, he has conducted the major international symphony orchestras – in Vienna, Munich, Dresden, Paris, Amsterdam, London, Rome, Chicago, Cleveland and Israel.

Since his debut in 2006, a variety of programmatic themes have emerged in his work together with the Berliner Philharmoniker. These include work on the orchestra’s core Classical-Romantic repertoire. Unjustly forgotten composers are another of Petrenko’s interests.

In opera performances with the Berliner Philharmoniker, Richard Strauss’ Die Frau ohne Schatten and Elektra have recently attracted attention.