Mahler Festival: Budapest Festival Orchestra and Iván Fischer in Mahlers Symphony No. 5 (English)

Main Hall 13 mei 2025 20.15 uur

Budapest Festival Orchestra

Iván Fischer conductor

Anna Lucia Richter mezzo-soprano

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Kindertotenlieder (1901-04)

Nun will die Sonn’ so hell aufgeh’n

Nun seh’ ich wohl, warum so dunkle Flammen

Wenn dein Mütterlein

Oft denk’ ich, sie sind nur ausgegangen

In diesem Wetter, in diesem Braus

interval ± 8.45PM

Symphony No. 5 in C sharp minor (1901-02, various revisions)

I Trauermarsch: In gemessenem Schritt. Streng. Wie ein Kondukt

Stürmisch bewegt, mit grösster Vehemenz

II Scherzo. Kräftig, nicht zu schnell

III Adagietto: Sehr langsam

Rondo – Finale: Allegro – Allegro giocoso. Frisch

end ± 10.30PM

Budapest Festival Orchestra

Iván Fischer conductor

Anna Lucia Richter mezzo-soprano

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Kindertotenlieder (1901-04)

Nun will die Sonn’ so hell aufgeh’n

Nun seh’ ich wohl, warum so dunkle Flammen

Wenn dein Mütterlein

Oft denk’ ich, sie sind nur ausgegangen

In diesem Wetter, in diesem Braus

interval ± 8.45PM

Symphony No. 5 in C sharp minor (1901-02, various revisions)

I Trauermarsch: In gemessenem Schritt. Streng. Wie ein Kondukt

Stürmisch bewegt, mit grösster Vehemenz

II Scherzo. Kräftig, nicht zu schnell

III Adagietto: Sehr langsam

Rondo – Finale: Allegro – Allegro giocoso. Frisch

end ± 10.30PM

Toelichting

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Kindertotenlieder

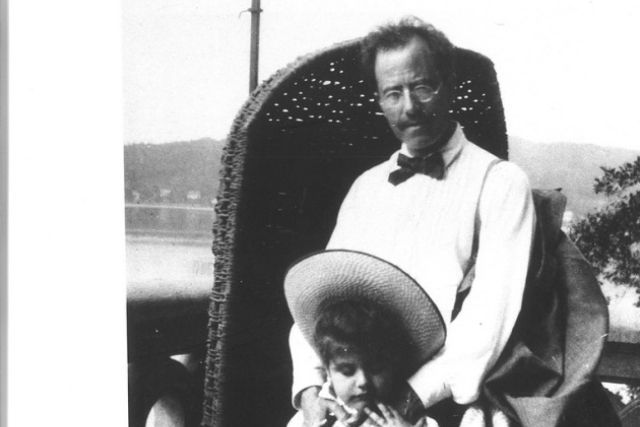

Friedrich Rückert (1788-1866) wrote more than four hundred poems in his attempt to come to terms with the deaths of his two children. Gustav Mahler chose five of these poems; he wrote the first three of his Kindertotenlieder in the summer of 1901 in Maiernigg. The two remaining songs were composed in 1904, during his summer holiday. In the intervening years, Mahler had married Alma Maria Schindler, and on 30 November 1902, their daughter, Maria, nicknamed Putzi, was born. Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder (Songs on the Death of Children) are often seen as foreshadowing Putzi’s death on 5 July 1907, an idea derived from Alma Mahler’s book, Gustav Mahler, Memories and Letters (1946), in which she blames her husband for tempting fate by choosing these Rückert poems. A more likely scenario, however, is that Mahler simply felt a purely expressive empathy with a man who was coping with the loss of his children. In this, Mahler also drew on his childhood memories, especially those of the death of his brother.

Friedrich Rückert (1788-1866) wrote more than four hundred poems in his attempt to come to terms with the deaths of his two children. Gustav Mahler chose five of these poems; he wrote the first three of his Kindertotenlieder in the summer of 1901 in Maiernigg. The two remaining songs were composed in 1904, during his summer holiday. In the intervening years, Mahler had married Alma Maria Schindler, and on 30 November 1902, their daughter, Maria, nicknamed Putzi, was born. Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder (Songs on the Death of Children) are often seen as foreshadowing Putzi’s death on 5 July 1907, an idea derived from Alma Mahler’s book, Gustav Mahler, Memories and Letters (1946), in which she blames her husband for tempting fate by choosing these Rückert poems. A more likely scenario, however, is that Mahler simply felt a purely expressive empathy with a man who was coping with the loss of his children. In this, Mahler also drew on his childhood memories, especially those of the death of his brother.

In Nun, die Sonn’ so hell aufgeh’n, the vocalist (usually a baritone or mezzo-soprano) subtly underlines the father’s crushing sadness. The second song, Nun seh’ ich wohl, is characterized by agitation, doubt and painful delusions. The highly recognizable state of denial is at the heart of the moving Wenn dein Mütterlein, in which the childlike simplicity of the melody recalls a Moravian folk song. In Oft denk’ ich, sie sind nur ausgegangen, the father imagines his children have simply gone on an extended hike in the mountains and are reluctant to return home. The closing measures are bathed in an all-encompassing, loving light. In the final song, however, despair and anger gain the upper hand. A devastating thunderstorm symbolizes the inner wrestling of the mourning parent. In the end, a tender lullaby emerges to offer heavenly solace.

Translation: Josh Dillon

In Nun, die Sonn’ so hell aufgeh’n, the vocalist (usually a baritone or mezzo-soprano) subtly underlines the father’s crushing sadness. The second song, Nun seh’ ich wohl, is characterized by agitation, doubt and painful delusions. The highly recognizable state of denial is at the heart of the moving Wenn dein Mütterlein, in which the childlike simplicity of the melody recalls a Moravian folk song. In Oft denk’ ich, sie sind nur ausgegangen, the father imagines his children have simply gone on an extended hike in the mountains and are reluctant to return home. The closing measures are bathed in an all-encompassing, loving light. In the final song, however, despair and anger gain the upper hand. A devastating thunderstorm symbolizes the inner wrestling of the mourning parent. In the end, a tender lullaby emerges to offer heavenly solace.

Translation: Josh Dillon

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Symphony No. 5

After having incorporated the human voice (chorus and/or soloist) in his Second, Third and Fourth Symphonies, it was in the Fifth that Gustav Mahler returned to a purely instrumental format. The scoring, however, is lavish and features an expansive percussion section (including Holzklapper, or clappers), four flautists (all of whom play the piccolo at one point), six horns, four trumpets, three trombones and a bass tuba. Mahler also calls for three oboes, three clarinets, and three bassoons (rather than the usual two), and employs the strings in möglichst zahlreicher Besetzung (with the largest number of players possible).

Favourable circumstances

For Mahler, 1901 was a favourable year. Indeed, his friend, the conductor Bruno Walter, recalls in his book on the composer that ‘[he was] feeling strong and equal to life…. Thus the Fifth Symphony is born, a work of strength and sound self-reliance, its face turned squarely towards life, and its basic mood one of optimism…. In the Fifth the world has now a masterpiece which shows its creator at the summit of his life, of his power, and of his ability.’ Mahler composed the first three movements in Maiernigg that summer, enjoying being able to work on new music amid the woods and alpine meadows of his villa-cum-composer’s cottage on the Wörthersee – an activity for which he normally lacked the necessary peace of mind when performing his duties as conductor and director of the Vienna Hofoper (later Staatsoper) during the concert season. That same summer he also wrote the five Rückert songs and his final Wunderhorn song, Der Tamboursg’sell, a soldier’s farewell march whose instrumental intermezzo can be heard in the funeral march of the Fifth Symphony. Although as late as July Mahler had described the work as ‘a rule-abiding symphony in four movements’, it would ultimately consist of five grouped into three large parts (Abteilungen).

The progression of the five movements

The symphony opens with a trumpet signal, soon accompanied by muted drum rolls, then alternates with melancholic, even unsettling, string melodies, with the addition of a good deal more brass. The numerous march rhythms and brass signals in Mahler’s œuvre can be traced to his earliest musical memories as a child in Iglau (now Jihlava), a Bohemian garrison town where he would hear the military band play and observe soldiers on parade. The march music in the Fifth Symphony is that of a funeral procession (Kondukt). Mahler reintroduces elements of the funeral march in the turbulent second movement, thereby creating great cohesion between the movements. At one point in the second movement, he explicitly writes the indication ‘im Tempo des ersten Satzes, Trauermarsch’ (in the tempo of the funeral march of the first movement). After a series of sparkling upsurges, the second movement eventually fades away inconclusively.

The first movement of the symphony Mahler completed was the middle one – a voluminous Scherzo underpinned by two quintessentially Austrian dances, the waltz and the ländler. Brimming with changing tempos and characters, it features a prominent horn solo, of which Mahler once remarked, ‘It is a human being in the full light of day, in the prime of his life.’ Serving as a turning point, the Scherzo bridges the foregoing, predominately darker, music with the final Abteilung, in which light and a lust for life unequivocally prevail.

After having incorporated the human voice (chorus and/or soloist) in his Second, Third and Fourth Symphonies, it was in the Fifth that Gustav Mahler returned to a purely instrumental format. The scoring, however, is lavish and features an expansive percussion section (including Holzklapper, or clappers), four flautists (all of whom play the piccolo at one point), six horns, four trumpets, three trombones and a bass tuba. Mahler also calls for three oboes, three clarinets, and three bassoons (rather than the usual two), and employs the strings in möglichst zahlreicher Besetzung (with the largest number of players possible).

Favourable circumstances

For Mahler, 1901 was a favourable year. Indeed, his friend, the conductor Bruno Walter, recalls in his book on the composer that ‘[he was] feeling strong and equal to life…. Thus the Fifth Symphony is born, a work of strength and sound self-reliance, its face turned squarely towards life, and its basic mood one of optimism…. In the Fifth the world has now a masterpiece which shows its creator at the summit of his life, of his power, and of his ability.’ Mahler composed the first three movements in Maiernigg that summer, enjoying being able to work on new music amid the woods and alpine meadows of his villa-cum-composer’s cottage on the Wörthersee – an activity for which he normally lacked the necessary peace of mind when performing his duties as conductor and director of the Vienna Hofoper (later Staatsoper) during the concert season. That same summer he also wrote the five Rückert songs and his final Wunderhorn song, Der Tamboursg’sell, a soldier’s farewell march whose instrumental intermezzo can be heard in the funeral march of the Fifth Symphony. Although as late as July Mahler had described the work as ‘a rule-abiding symphony in four movements’, it would ultimately consist of five grouped into three large parts (Abteilungen).

The progression of the five movements

The symphony opens with a trumpet signal, soon accompanied by muted drum rolls, then alternates with melancholic, even unsettling, string melodies, with the addition of a good deal more brass. The numerous march rhythms and brass signals in Mahler’s œuvre can be traced to his earliest musical memories as a child in Iglau (now Jihlava), a Bohemian garrison town where he would hear the military band play and observe soldiers on parade. The march music in the Fifth Symphony is that of a funeral procession (Kondukt). Mahler reintroduces elements of the funeral march in the turbulent second movement, thereby creating great cohesion between the movements. At one point in the second movement, he explicitly writes the indication ‘im Tempo des ersten Satzes, Trauermarsch’ (in the tempo of the funeral march of the first movement). After a series of sparkling upsurges, the second movement eventually fades away inconclusively.

The first movement of the symphony Mahler completed was the middle one – a voluminous Scherzo underpinned by two quintessentially Austrian dances, the waltz and the ländler. Brimming with changing tempos and characters, it features a prominent horn solo, of which Mahler once remarked, ‘It is a human being in the full light of day, in the prime of his life.’ Serving as a turning point, the Scherzo bridges the foregoing, predominately darker, music with the final Abteilung, in which light and a lust for life unequivocally prevail.

In November, during the early part of the 1901–2 opera season, Mahler – a bachelor of forty-one – met the twenty-two-year-old Alma Maria Schindler at a dinner party. Alma, then the student and lover of the thirty-year-old composer Alexander von Zemlinsky, captured Mahler’s heart. The Adagietto – the yearning fourth movement of the Fifth Symphony – would be his love letter to her: Mahler sent her the sheet music with no further explanation. The notes would tell her everything she needed to know, as the Concertgebouw Orchestra’s chief conductor Willem Mengelberg would later write in the score: ‘She understood him and wrote back, “Come!” Both of them told me this story.’ Accordingly, Mengelberg heard in the Adagietto ‘a love as it is born’. Gustav and Alma married on 9 March 1902, and their first daughter was born on 3 November. Although it would prove to be a tumultuous marriage, his union with ‘the most beautiful woman in Vienna’ was an initial boon to Mahler.

First performances

Scored solely for harp and string orchestra, the Adagietto leads attacca (without pause) into the Rondo-Finale for full orchestra. Together, they form what Mahler conceived as a single Abteilung. The many contrapuntal passages are a testament to Mahler’s close study of the fugues of Johann Sebastian Bach. Another defining element in this triumphant final movement is the distinctive brass chorale – an apparent homage to Anton Bruckner, with whom Mahler had studied harmony and counterpoint at the conservatory. With its radiant fanfares, the sparkling finale decisively prevails over the sombre mood with which the work opened.

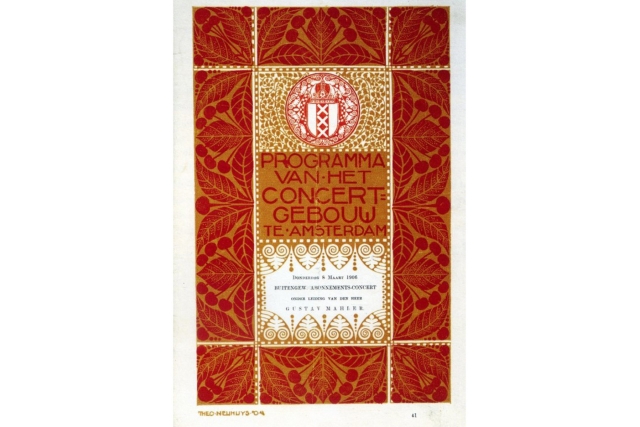

Mahler himself led the Gürzenich Orchestra in the premiere of his Symphony No. 5 in C‑sharp minor in Cologne on 18 October 1904. Aware of the groundbreaking nature of his latest work, he wrote to Alma, ‘The public – oh, heavens, what are they to make of this chaos of which new worlds are forever being engendered, only to crumble in ruin the moment after?’ The Dutch premiere was given by the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra in Scheveningen in 1905, and the Concertgebouw Orchestra soon followed suit in March 1906. Mahler travelled from Vienna to attend these performances, staying with the Mengelbergs at 107 Van Eeghenstraat as he had on his previous two visits to Amsterdam. The composer himself led the first performance of the Fifth at the Concertgebouw, with Mengelberg conducting seven more concerts – in Amsterdam, as well as Rotterdam, The Hague, Arnhem and Haarlem. Mahler would continue to revise the instrumentation of the Fifth Symphony until the year he died.

Translation: Josh Dillon

In November, during the early part of the 1901–2 opera season, Mahler – a bachelor of forty-one – met the twenty-two-year-old Alma Maria Schindler at a dinner party. Alma, then the student and lover of the thirty-year-old composer Alexander von Zemlinsky, captured Mahler’s heart. The Adagietto – the yearning fourth movement of the Fifth Symphony – would be his love letter to her: Mahler sent her the sheet music with no further explanation. The notes would tell her everything she needed to know, as the Concertgebouw Orchestra’s chief conductor Willem Mengelberg would later write in the score: ‘She understood him and wrote back, “Come!” Both of them told me this story.’ Accordingly, Mengelberg heard in the Adagietto ‘a love as it is born’. Gustav and Alma married on 9 March 1902, and their first daughter was born on 3 November. Although it would prove to be a tumultuous marriage, his union with ‘the most beautiful woman in Vienna’ was an initial boon to Mahler.

First performances

Scored solely for harp and string orchestra, the Adagietto leads attacca (without pause) into the Rondo-Finale for full orchestra. Together, they form what Mahler conceived as a single Abteilung. The many contrapuntal passages are a testament to Mahler’s close study of the fugues of Johann Sebastian Bach. Another defining element in this triumphant final movement is the distinctive brass chorale – an apparent homage to Anton Bruckner, with whom Mahler had studied harmony and counterpoint at the conservatory. With its radiant fanfares, the sparkling finale decisively prevails over the sombre mood with which the work opened.

Mahler himself led the Gürzenich Orchestra in the premiere of his Symphony No. 5 in C‑sharp minor in Cologne on 18 October 1904. Aware of the groundbreaking nature of his latest work, he wrote to Alma, ‘The public – oh, heavens, what are they to make of this chaos of which new worlds are forever being engendered, only to crumble in ruin the moment after?’ The Dutch premiere was given by the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra in Scheveningen in 1905, and the Concertgebouw Orchestra soon followed suit in March 1906. Mahler travelled from Vienna to attend these performances, staying with the Mengelbergs at 107 Van Eeghenstraat as he had on his previous two visits to Amsterdam. The composer himself led the first performance of the Fifth at the Concertgebouw, with Mengelberg conducting seven more concerts – in Amsterdam, as well as Rotterdam, The Hague, Arnhem and Haarlem. Mahler would continue to revise the instrumentation of the Fifth Symphony until the year he died.

Translation: Josh Dillon

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Kindertotenlieder

Friedrich Rückert (1788-1866) wrote more than four hundred poems in his attempt to come to terms with the deaths of his two children. Gustav Mahler chose five of these poems; he wrote the first three of his Kindertotenlieder in the summer of 1901 in Maiernigg. The two remaining songs were composed in 1904, during his summer holiday. In the intervening years, Mahler had married Alma Maria Schindler, and on 30 November 1902, their daughter, Maria, nicknamed Putzi, was born. Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder (Songs on the Death of Children) are often seen as foreshadowing Putzi’s death on 5 July 1907, an idea derived from Alma Mahler’s book, Gustav Mahler, Memories and Letters (1946), in which she blames her husband for tempting fate by choosing these Rückert poems. A more likely scenario, however, is that Mahler simply felt a purely expressive empathy with a man who was coping with the loss of his children. In this, Mahler also drew on his childhood memories, especially those of the death of his brother.

Friedrich Rückert (1788-1866) wrote more than four hundred poems in his attempt to come to terms with the deaths of his two children. Gustav Mahler chose five of these poems; he wrote the first three of his Kindertotenlieder in the summer of 1901 in Maiernigg. The two remaining songs were composed in 1904, during his summer holiday. In the intervening years, Mahler had married Alma Maria Schindler, and on 30 November 1902, their daughter, Maria, nicknamed Putzi, was born. Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder (Songs on the Death of Children) are often seen as foreshadowing Putzi’s death on 5 July 1907, an idea derived from Alma Mahler’s book, Gustav Mahler, Memories and Letters (1946), in which she blames her husband for tempting fate by choosing these Rückert poems. A more likely scenario, however, is that Mahler simply felt a purely expressive empathy with a man who was coping with the loss of his children. In this, Mahler also drew on his childhood memories, especially those of the death of his brother.

In Nun, die Sonn’ so hell aufgeh’n, the vocalist (usually a baritone or mezzo-soprano) subtly underlines the father’s crushing sadness. The second song, Nun seh’ ich wohl, is characterized by agitation, doubt and painful delusions. The highly recognizable state of denial is at the heart of the moving Wenn dein Mütterlein, in which the childlike simplicity of the melody recalls a Moravian folk song. In Oft denk’ ich, sie sind nur ausgegangen, the father imagines his children have simply gone on an extended hike in the mountains and are reluctant to return home. The closing measures are bathed in an all-encompassing, loving light. In the final song, however, despair and anger gain the upper hand. A devastating thunderstorm symbolizes the inner wrestling of the mourning parent. In the end, a tender lullaby emerges to offer heavenly solace.

Translation: Josh Dillon

In Nun, die Sonn’ so hell aufgeh’n, the vocalist (usually a baritone or mezzo-soprano) subtly underlines the father’s crushing sadness. The second song, Nun seh’ ich wohl, is characterized by agitation, doubt and painful delusions. The highly recognizable state of denial is at the heart of the moving Wenn dein Mütterlein, in which the childlike simplicity of the melody recalls a Moravian folk song. In Oft denk’ ich, sie sind nur ausgegangen, the father imagines his children have simply gone on an extended hike in the mountains and are reluctant to return home. The closing measures are bathed in an all-encompassing, loving light. In the final song, however, despair and anger gain the upper hand. A devastating thunderstorm symbolizes the inner wrestling of the mourning parent. In the end, a tender lullaby emerges to offer heavenly solace.

Translation: Josh Dillon

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Symphony No. 5

After having incorporated the human voice (chorus and/or soloist) in his Second, Third and Fourth Symphonies, it was in the Fifth that Gustav Mahler returned to a purely instrumental format. The scoring, however, is lavish and features an expansive percussion section (including Holzklapper, or clappers), four flautists (all of whom play the piccolo at one point), six horns, four trumpets, three trombones and a bass tuba. Mahler also calls for three oboes, three clarinets, and three bassoons (rather than the usual two), and employs the strings in möglichst zahlreicher Besetzung (with the largest number of players possible).

Favourable circumstances

For Mahler, 1901 was a favourable year. Indeed, his friend, the conductor Bruno Walter, recalls in his book on the composer that ‘[he was] feeling strong and equal to life…. Thus the Fifth Symphony is born, a work of strength and sound self-reliance, its face turned squarely towards life, and its basic mood one of optimism…. In the Fifth the world has now a masterpiece which shows its creator at the summit of his life, of his power, and of his ability.’ Mahler composed the first three movements in Maiernigg that summer, enjoying being able to work on new music amid the woods and alpine meadows of his villa-cum-composer’s cottage on the Wörthersee – an activity for which he normally lacked the necessary peace of mind when performing his duties as conductor and director of the Vienna Hofoper (later Staatsoper) during the concert season. That same summer he also wrote the five Rückert songs and his final Wunderhorn song, Der Tamboursg’sell, a soldier’s farewell march whose instrumental intermezzo can be heard in the funeral march of the Fifth Symphony. Although as late as July Mahler had described the work as ‘a rule-abiding symphony in four movements’, it would ultimately consist of five grouped into three large parts (Abteilungen).

The progression of the five movements

The symphony opens with a trumpet signal, soon accompanied by muted drum rolls, then alternates with melancholic, even unsettling, string melodies, with the addition of a good deal more brass. The numerous march rhythms and brass signals in Mahler’s œuvre can be traced to his earliest musical memories as a child in Iglau (now Jihlava), a Bohemian garrison town where he would hear the military band play and observe soldiers on parade. The march music in the Fifth Symphony is that of a funeral procession (Kondukt). Mahler reintroduces elements of the funeral march in the turbulent second movement, thereby creating great cohesion between the movements. At one point in the second movement, he explicitly writes the indication ‘im Tempo des ersten Satzes, Trauermarsch’ (in the tempo of the funeral march of the first movement). After a series of sparkling upsurges, the second movement eventually fades away inconclusively.

The first movement of the symphony Mahler completed was the middle one – a voluminous Scherzo underpinned by two quintessentially Austrian dances, the waltz and the ländler. Brimming with changing tempos and characters, it features a prominent horn solo, of which Mahler once remarked, ‘It is a human being in the full light of day, in the prime of his life.’ Serving as a turning point, the Scherzo bridges the foregoing, predominately darker, music with the final Abteilung, in which light and a lust for life unequivocally prevail.

After having incorporated the human voice (chorus and/or soloist) in his Second, Third and Fourth Symphonies, it was in the Fifth that Gustav Mahler returned to a purely instrumental format. The scoring, however, is lavish and features an expansive percussion section (including Holzklapper, or clappers), four flautists (all of whom play the piccolo at one point), six horns, four trumpets, three trombones and a bass tuba. Mahler also calls for three oboes, three clarinets, and three bassoons (rather than the usual two), and employs the strings in möglichst zahlreicher Besetzung (with the largest number of players possible).

Favourable circumstances

For Mahler, 1901 was a favourable year. Indeed, his friend, the conductor Bruno Walter, recalls in his book on the composer that ‘[he was] feeling strong and equal to life…. Thus the Fifth Symphony is born, a work of strength and sound self-reliance, its face turned squarely towards life, and its basic mood one of optimism…. In the Fifth the world has now a masterpiece which shows its creator at the summit of his life, of his power, and of his ability.’ Mahler composed the first three movements in Maiernigg that summer, enjoying being able to work on new music amid the woods and alpine meadows of his villa-cum-composer’s cottage on the Wörthersee – an activity for which he normally lacked the necessary peace of mind when performing his duties as conductor and director of the Vienna Hofoper (later Staatsoper) during the concert season. That same summer he also wrote the five Rückert songs and his final Wunderhorn song, Der Tamboursg’sell, a soldier’s farewell march whose instrumental intermezzo can be heard in the funeral march of the Fifth Symphony. Although as late as July Mahler had described the work as ‘a rule-abiding symphony in four movements’, it would ultimately consist of five grouped into three large parts (Abteilungen).

The progression of the five movements

The symphony opens with a trumpet signal, soon accompanied by muted drum rolls, then alternates with melancholic, even unsettling, string melodies, with the addition of a good deal more brass. The numerous march rhythms and brass signals in Mahler’s œuvre can be traced to his earliest musical memories as a child in Iglau (now Jihlava), a Bohemian garrison town where he would hear the military band play and observe soldiers on parade. The march music in the Fifth Symphony is that of a funeral procession (Kondukt). Mahler reintroduces elements of the funeral march in the turbulent second movement, thereby creating great cohesion between the movements. At one point in the second movement, he explicitly writes the indication ‘im Tempo des ersten Satzes, Trauermarsch’ (in the tempo of the funeral march of the first movement). After a series of sparkling upsurges, the second movement eventually fades away inconclusively.

The first movement of the symphony Mahler completed was the middle one – a voluminous Scherzo underpinned by two quintessentially Austrian dances, the waltz and the ländler. Brimming with changing tempos and characters, it features a prominent horn solo, of which Mahler once remarked, ‘It is a human being in the full light of day, in the prime of his life.’ Serving as a turning point, the Scherzo bridges the foregoing, predominately darker, music with the final Abteilung, in which light and a lust for life unequivocally prevail.

In November, during the early part of the 1901–2 opera season, Mahler – a bachelor of forty-one – met the twenty-two-year-old Alma Maria Schindler at a dinner party. Alma, then the student and lover of the thirty-year-old composer Alexander von Zemlinsky, captured Mahler’s heart. The Adagietto – the yearning fourth movement of the Fifth Symphony – would be his love letter to her: Mahler sent her the sheet music with no further explanation. The notes would tell her everything she needed to know, as the Concertgebouw Orchestra’s chief conductor Willem Mengelberg would later write in the score: ‘She understood him and wrote back, “Come!” Both of them told me this story.’ Accordingly, Mengelberg heard in the Adagietto ‘a love as it is born’. Gustav and Alma married on 9 March 1902, and their first daughter was born on 3 November. Although it would prove to be a tumultuous marriage, his union with ‘the most beautiful woman in Vienna’ was an initial boon to Mahler.

First performances

Scored solely for harp and string orchestra, the Adagietto leads attacca (without pause) into the Rondo-Finale for full orchestra. Together, they form what Mahler conceived as a single Abteilung. The many contrapuntal passages are a testament to Mahler’s close study of the fugues of Johann Sebastian Bach. Another defining element in this triumphant final movement is the distinctive brass chorale – an apparent homage to Anton Bruckner, with whom Mahler had studied harmony and counterpoint at the conservatory. With its radiant fanfares, the sparkling finale decisively prevails over the sombre mood with which the work opened.

Mahler himself led the Gürzenich Orchestra in the premiere of his Symphony No. 5 in C‑sharp minor in Cologne on 18 October 1904. Aware of the groundbreaking nature of his latest work, he wrote to Alma, ‘The public – oh, heavens, what are they to make of this chaos of which new worlds are forever being engendered, only to crumble in ruin the moment after?’ The Dutch premiere was given by the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra in Scheveningen in 1905, and the Concertgebouw Orchestra soon followed suit in March 1906. Mahler travelled from Vienna to attend these performances, staying with the Mengelbergs at 107 Van Eeghenstraat as he had on his previous two visits to Amsterdam. The composer himself led the first performance of the Fifth at the Concertgebouw, with Mengelberg conducting seven more concerts – in Amsterdam, as well as Rotterdam, The Hague, Arnhem and Haarlem. Mahler would continue to revise the instrumentation of the Fifth Symphony until the year he died.

Translation: Josh Dillon

In November, during the early part of the 1901–2 opera season, Mahler – a bachelor of forty-one – met the twenty-two-year-old Alma Maria Schindler at a dinner party. Alma, then the student and lover of the thirty-year-old composer Alexander von Zemlinsky, captured Mahler’s heart. The Adagietto – the yearning fourth movement of the Fifth Symphony – would be his love letter to her: Mahler sent her the sheet music with no further explanation. The notes would tell her everything she needed to know, as the Concertgebouw Orchestra’s chief conductor Willem Mengelberg would later write in the score: ‘She understood him and wrote back, “Come!” Both of them told me this story.’ Accordingly, Mengelberg heard in the Adagietto ‘a love as it is born’. Gustav and Alma married on 9 March 1902, and their first daughter was born on 3 November. Although it would prove to be a tumultuous marriage, his union with ‘the most beautiful woman in Vienna’ was an initial boon to Mahler.

First performances

Scored solely for harp and string orchestra, the Adagietto leads attacca (without pause) into the Rondo-Finale for full orchestra. Together, they form what Mahler conceived as a single Abteilung. The many contrapuntal passages are a testament to Mahler’s close study of the fugues of Johann Sebastian Bach. Another defining element in this triumphant final movement is the distinctive brass chorale – an apparent homage to Anton Bruckner, with whom Mahler had studied harmony and counterpoint at the conservatory. With its radiant fanfares, the sparkling finale decisively prevails over the sombre mood with which the work opened.

Mahler himself led the Gürzenich Orchestra in the premiere of his Symphony No. 5 in C‑sharp minor in Cologne on 18 October 1904. Aware of the groundbreaking nature of his latest work, he wrote to Alma, ‘The public – oh, heavens, what are they to make of this chaos of which new worlds are forever being engendered, only to crumble in ruin the moment after?’ The Dutch premiere was given by the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra in Scheveningen in 1905, and the Concertgebouw Orchestra soon followed suit in March 1906. Mahler travelled from Vienna to attend these performances, staying with the Mengelbergs at 107 Van Eeghenstraat as he had on his previous two visits to Amsterdam. The composer himself led the first performance of the Fifth at the Concertgebouw, with Mengelberg conducting seven more concerts – in Amsterdam, as well as Rotterdam, The Hague, Arnhem and Haarlem. Mahler would continue to revise the instrumentation of the Fifth Symphony until the year he died.

Translation: Josh Dillon

Biografie

Budapest Festival Orchestra, orchestra

In 1983, Iván Fischer made a dream come true when he and Zoltán Kocsis founded the Budapest Festival Orchestra. From its very beginning, the Hungarian company’s ambition was to offer performances of the highest level and to serve the public in different ways.

The orchestra is famous for its innovative programming, including surprise concerts and musical marathons.

The Budapest Festival Orchestra performs regularly in major concert halls including The Concertgebouw, where they played Mahler’s Ninth Symphony in 2013, Carnegie Hall and Lincoln Center in New York, the Musikverein in Vienna and the Royal Albert Hall in London.

The orchestra was nominated for a Grammy Award in 2013 for their CD of Mahler’s First Symphony. A year later the Budapest Festival Orchestra won a Diapason d’Or and the Italian ‘Toblacher Komponierhäuschen’ prize for their recording of his Fifth Symphony.

Iván Fischer, conductor

Iván Fischer studied piano, violin, cello and composition in Budapest before studying conducting with Hans Swarowsky and Nikolaus Harnoncourt in Vienna and Salzburg. Fischer is the founder and Chief Conductor of the Budapest Festival Orchestra, and Honorary Conductor of Berlin’s Konzerthausorchester and Konzerthaus, where he was Chief Conductor between 2012 and 2018.

Since 2018 he has been the Vicenza Opera Festival’s Artistic Director, and since 2021-2022 has been an Honorary Guest Conductor with the Concertgebouw Orchestra. He is a frequent guest with the Berliner Philharmoniker, New York Philharmonic and other leading orchestras. He has conducted opera productions in the Wiener Staatsoper, London’s Royal Opera House Covent Garden, the Opéra de Paris and others.

Fischer is the founder of Hungary’s Gustav Mahler Society and patron of the British Kodály Academy. In 2013 he became an honorary member of the Royal Academy of Music in London.

Anna Lucia Richter, mezzo-soprano

Anna Lucia Richter first performed in the girls’ choir of the Dom cathedral in Cologne. Her first lessons were with her mother, Regina Dohmen, and she studied later with Kurt Widmer and Klesie Kelly-Moog, as well as with Margreet Honig, Edith Wiens and Christoph Prégardien.

The singer has won a string of prizes, among them a Borletti-Buitoni Trust Award in 2016.

From the spring of 2020 she was guided by Tamar Rachum in the transition from soprano to mezzo-soprano, an important step rich in new opportunities. She was the alto soloist in Mahler’s Second Symphony with the Bamberger Symphoniker, conducted by Jakub Hrůša.

Her repertoire reaches from Monteverdi and Bach, and late-Romantics such as Mahler and Berlioz, to contemporary composers such as Holliger and Rihm.

Richter made her Concertgebouw debut in 2014 in the Recital Hall, and she has appeared there and in the Main Hall many times since then.