Mahler Festival: Budapest Festival Orchestra and Iván Fischer in Mahler's Symphony No. 2 (English)

Main Hall 11 mei 2025 11.00 uur

Budapest Festival Orchestra

Netherlands Radio Choir choral conductor: Peter Dijkstra

Christiane Karg soprano

Anna Lucia Richter mezzo-soprano

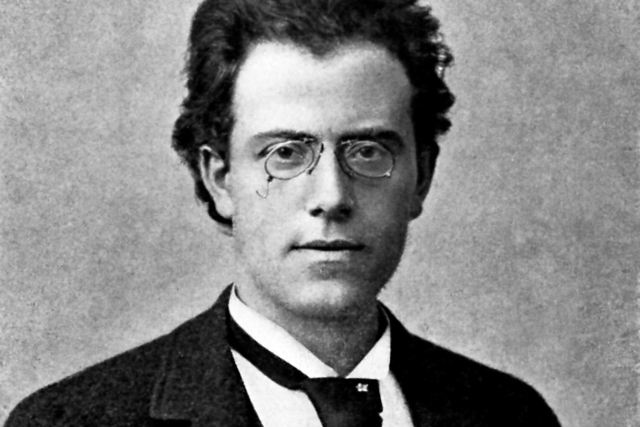

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Symphony No. 2 in C minor ‘Auferstehung’ (1888-94, revision 1903)

for orchestra, soprano, contralto and mixed choir

Allegro maestoso

Andante moderato

In ruhig fliessender Bewegung

‘Urlicht’ – Sehr feierlich, aber schlicht

Im Tempo des Scherzos

no interval

end ± 12.30AM

Budapest Festival Orchestra

Netherlands Radio Choir choral conductor: Peter Dijkstra

Christiane Karg soprano

Anna Lucia Richter mezzo-soprano

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Symphony No. 2 in C minor ‘Auferstehung’ (1888-94, revision 1903)

for orchestra, soprano, contralto and mixed choir

Allegro maestoso

Andante moderato

In ruhig fliessender Bewegung

‘Urlicht’ – Sehr feierlich, aber schlicht

Im Tempo des Scherzos

no interval

end ± 12.30AM

Toelichting

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Symphony No. 2

Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 1 (1884–8), also known as the ‘Titan’, is a symphonic portrait of a ‘hero’ who bears a close resemblance to the young Mahler – a loner who grapples with himself and with the world, whose life struggle ‘dall’inferno al paradiso’, as Mahler called it in an early version, is celebrated only at the last minute with a conquest of self. Yet, remarkably, it is precisely this alter ego that Mahler finishes off in his Second Symphony. ‘I have called the first movement “Todtenfeier” [Funeral Pomp],’ he wrote to the composer and music critic Max Marschalk, ‘and it may interest you to know that it is the hero of my D major symphony who is being borne to his grave, his life being reflected as in a clear mirror. Here, too, the great question is asked: What did you live for? Why did you suffer? Is it all only a vast, terrifying joke? We have to answer these questions somehow if we are to go on living – indeed, even if we are only to go on dying! The person in whose life this call has resounded, even if it was only once, must give an answer. And it is this answer that I give in the last movement.’

The letter to Marschalk gives the impression, between the lines in any case, that Mahler felt he had outgrown the egocentric obsessions of his own heroic years, demonstrably sealing his spiritual evolution with the interment of a former self. The most individual stirrings of the soul in the First Symphony are no match for the seasoned universal questions of humanity in the Second.

Indeed, the transformation is audible. Although he did write one movement of the Second Symphony the same year he completed the First, Mahler proving once again that he is a master of the grotesque, the Second Symphony lacks the impetuous, eccentrically ambiguous elan of its predecessor, which with all its pathos truly was a youthful work. Nearly an hour and a half long and scored for a giant orchestra with a large brass section, Fernorchester, large choir, and soprano and contralto parts, the Second Symphony rivals Beethoven’s Ninth (1823–4). Deliberately and with Beethoven in mind, Mahler transcends the symphonic form, which had become a straitjacket for him in his attempt to express the highest ideas, as he would later tell his friend, the violinist Natalie Bauer-Lechner; ultimately, he had to resort to the use of words, since he simply ‘could not manage any longer with notes alone’.

Two of the five movements contain vocal parts, and a third is based on Mahler’s lied output. The fourth movement (‘Urlicht’) is a lied from Des Knaben Wunderhorn, the early nineteenth-century German folk song anthology that left an indelible mark on Mahler’s lieder and symphonies. The third movement, a scherzo, is an instrumental version of Mahler’s hilarious Wunderhorn lied Des Antonius von Padua Fischpredigt, in which St Anthony preaches to the fish with naive and pointless devotion – a wasted effort indeed, given that his congregation proves to be as deaf as the human variety. Following an earth-shattering musical rendering of Judgement Day, the colossal choral finale concludes with a setting of Klopstock’s hopeful ‘Resurrection’ ode.

The means deployed are complementary to the work’s thematic breadth. The narcissistic ‘Sturm und Drang’ of the First Symphony is relentlessly overcompensated for by an emphasis, lovingly placed, on the human condition. The misunderstood artist has become a humanist who, out of compassion, ponders the plight of his fellow man, and like a brother in distress, whispers a message of hope in his ear on Klopstock’s wings, promising resurrection and immortality. Mahler’s missionary zeal is so great that he even adds a few of his own lines of consoling verse to Klopstock’s text: ‘O glaube: Du wardst nicht umsonst geboren! Hast nicht umsonst gelebt, gelitten!’ (O believe, You were not born for nothing! Have not lived for nothing, Nor suffered!) The hero of the First Symphony is buried because a new one has risen up, a man who fraternises with his fellow men.

Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 1 (1884–8), also known as the ‘Titan’, is a symphonic portrait of a ‘hero’ who bears a close resemblance to the young Mahler – a loner who grapples with himself and with the world, whose life struggle ‘dall’inferno al paradiso’, as Mahler called it in an early version, is celebrated only at the last minute with a conquest of self. Yet, remarkably, it is precisely this alter ego that Mahler finishes off in his Second Symphony. ‘I have called the first movement “Todtenfeier” [Funeral Pomp],’ he wrote to the composer and music critic Max Marschalk, ‘and it may interest you to know that it is the hero of my D major symphony who is being borne to his grave, his life being reflected as in a clear mirror. Here, too, the great question is asked: What did you live for? Why did you suffer? Is it all only a vast, terrifying joke? We have to answer these questions somehow if we are to go on living – indeed, even if we are only to go on dying! The person in whose life this call has resounded, even if it was only once, must give an answer. And it is this answer that I give in the last movement.’

The letter to Marschalk gives the impression, between the lines in any case, that Mahler felt he had outgrown the egocentric obsessions of his own heroic years, demonstrably sealing his spiritual evolution with the interment of a former self. The most individual stirrings of the soul in the First Symphony are no match for the seasoned universal questions of humanity in the Second.

Indeed, the transformation is audible. Although he did write one movement of the Second Symphony the same year he completed the First, Mahler proving once again that he is a master of the grotesque, the Second Symphony lacks the impetuous, eccentrically ambiguous elan of its predecessor, which with all its pathos truly was a youthful work. Nearly an hour and a half long and scored for a giant orchestra with a large brass section, Fernorchester, large choir, and soprano and contralto parts, the Second Symphony rivals Beethoven’s Ninth (1823–4). Deliberately and with Beethoven in mind, Mahler transcends the symphonic form, which had become a straitjacket for him in his attempt to express the highest ideas, as he would later tell his friend, the violinist Natalie Bauer-Lechner; ultimately, he had to resort to the use of words, since he simply ‘could not manage any longer with notes alone’.

Two of the five movements contain vocal parts, and a third is based on Mahler’s lied output. The fourth movement (‘Urlicht’) is a lied from Des Knaben Wunderhorn, the early nineteenth-century German folk song anthology that left an indelible mark on Mahler’s lieder and symphonies. The third movement, a scherzo, is an instrumental version of Mahler’s hilarious Wunderhorn lied Des Antonius von Padua Fischpredigt, in which St Anthony preaches to the fish with naive and pointless devotion – a wasted effort indeed, given that his congregation proves to be as deaf as the human variety. Following an earth-shattering musical rendering of Judgement Day, the colossal choral finale concludes with a setting of Klopstock’s hopeful ‘Resurrection’ ode.

The means deployed are complementary to the work’s thematic breadth. The narcissistic ‘Sturm und Drang’ of the First Symphony is relentlessly overcompensated for by an emphasis, lovingly placed, on the human condition. The misunderstood artist has become a humanist who, out of compassion, ponders the plight of his fellow man, and like a brother in distress, whispers a message of hope in his ear on Klopstock’s wings, promising resurrection and immortality. Mahler’s missionary zeal is so great that he even adds a few of his own lines of consoling verse to Klopstock’s text: ‘O glaube: Du wardst nicht umsonst geboren! Hast nicht umsonst gelebt, gelitten!’ (O believe, You were not born for nothing! Have not lived for nothing, Nor suffered!) The hero of the First Symphony is buried because a new one has risen up, a man who fraternises with his fellow men.

Like the first version of the First Symphony (that included ‘Blumine’, which Mahler later discarded), the Second Symphony is a five-movement work that appears to be divided into two Teile or Abteilungen (parts or units). Mahler suggested that they should be separated by at least a five-minute pause. The first Abteilung is made up of the funeral march (Allegro maestoso), originally composed as a self-contained whole; the break is proceeded by the instrumental ländler (Andante moderato) and a scherzo (‘In ruhig fliessender Bewegung’), directly followed by the hymn-like ‘Urlicht’ for solo contralto and the monumental finale.

As Mahler wrote to Marschalk, the first movement, sketched in September 1888, originally bore the name ‘Todtenfeier’. As he had done with the First Symphony, Mahler called it a ‘symphonic poem’, albeit only after having crossed out the original title ‘Symphony in C minor’. According to statements he made to Natalie Bauer-Lechner, Mahler had made sketches of the Scherzo and Andante in Leipzig earlier in 1888, which he developed in Steinbach in 1893. Yet it was not until March 1894 that the symphony actually evolved into a fully fledged work. It was during the great conductor Hans von Bülow’s memorial service in Michaelskirche in Hamburg that Mahler heard Klopstock’s poem ‘The Resurrection’, which provided him with the revelation he needed to overcome his artistic and philosophical impasse. A few months later, on 25 July 1894, Mahler could write to his friend Arnold Berliner to tell him that he had completed the finale, saying, ‘Es ist das Bedeutendste, was ich bis jetzt gemacht habe’ (It is the greatest thing I have done so far).

Without yielding to the drudgery of the symphonic tradition, Mahler seems to seek a connection with his musical predecessors, more so than he had done in the First Symphony. The model of the choral symphony, explicitly borrowed from Beethoven, is one example, just as the technique of motivic fragmentation that emerges in the Second is frequently reminiscent of Beethoven. Echoes of Bruckner and Wagner are clearly audible. In the finale, Mahler combines the Dies irae theme – which Berlioz had used in his Symphonie fantastique (1830) – with the clamorous pandemonium in the orchestra depicting the Resurrection, followed by blasts in the brass featuring the trumpets of the apocalypse, headed ‘Der grosse Appell!’ (The grand summons!) in the manuscript. With all its show of genius, this is unadulterated figurative programme music.

All the more impressive is Mahler’s ability to incorporate a profusion of atmospheres and idioms (e.g. march, chorale, ländler, Naturlaut and lied) into a symphonic form in which extreme dramatic contrasts bolster, rather than weaken, the unity of the work. At first glance, the five movements are like neighbouring, yet independent, republics on a vast, savage symphonic continent. They are worlds apart in terms of their respective length, instrumentation and tone. Although constructive elements like tonal and thematic relationships underpin either covertly or audibly their latent coherence, it is primarily the all-pervasive idea of the horror of death which holds this enormous work together. This fear ultimately becomes so unbearable that it is man’s steadfast belief in an escape which is his only consolation.

Translation: Josh Dillon

Like the first version of the First Symphony (that included ‘Blumine’, which Mahler later discarded), the Second Symphony is a five-movement work that appears to be divided into two Teile or Abteilungen (parts or units). Mahler suggested that they should be separated by at least a five-minute pause. The first Abteilung is made up of the funeral march (Allegro maestoso), originally composed as a self-contained whole; the break is proceeded by the instrumental ländler (Andante moderato) and a scherzo (‘In ruhig fliessender Bewegung’), directly followed by the hymn-like ‘Urlicht’ for solo contralto and the monumental finale.

As Mahler wrote to Marschalk, the first movement, sketched in September 1888, originally bore the name ‘Todtenfeier’. As he had done with the First Symphony, Mahler called it a ‘symphonic poem’, albeit only after having crossed out the original title ‘Symphony in C minor’. According to statements he made to Natalie Bauer-Lechner, Mahler had made sketches of the Scherzo and Andante in Leipzig earlier in 1888, which he developed in Steinbach in 1893. Yet it was not until March 1894 that the symphony actually evolved into a fully fledged work. It was during the great conductor Hans von Bülow’s memorial service in Michaelskirche in Hamburg that Mahler heard Klopstock’s poem ‘The Resurrection’, which provided him with the revelation he needed to overcome his artistic and philosophical impasse. A few months later, on 25 July 1894, Mahler could write to his friend Arnold Berliner to tell him that he had completed the finale, saying, ‘Es ist das Bedeutendste, was ich bis jetzt gemacht habe’ (It is the greatest thing I have done so far).

Without yielding to the drudgery of the symphonic tradition, Mahler seems to seek a connection with his musical predecessors, more so than he had done in the First Symphony. The model of the choral symphony, explicitly borrowed from Beethoven, is one example, just as the technique of motivic fragmentation that emerges in the Second is frequently reminiscent of Beethoven. Echoes of Bruckner and Wagner are clearly audible. In the finale, Mahler combines the Dies irae theme – which Berlioz had used in his Symphonie fantastique (1830) – with the clamorous pandemonium in the orchestra depicting the Resurrection, followed by blasts in the brass featuring the trumpets of the apocalypse, headed ‘Der grosse Appell!’ (The grand summons!) in the manuscript. With all its show of genius, this is unadulterated figurative programme music.

All the more impressive is Mahler’s ability to incorporate a profusion of atmospheres and idioms (e.g. march, chorale, ländler, Naturlaut and lied) into a symphonic form in which extreme dramatic contrasts bolster, rather than weaken, the unity of the work. At first glance, the five movements are like neighbouring, yet independent, republics on a vast, savage symphonic continent. They are worlds apart in terms of their respective length, instrumentation and tone. Although constructive elements like tonal and thematic relationships underpin either covertly or audibly their latent coherence, it is primarily the all-pervasive idea of the horror of death which holds this enormous work together. This fear ultimately becomes so unbearable that it is man’s steadfast belief in an escape which is his only consolation.

Translation: Josh Dillon

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Symphony No. 2

Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 1 (1884–8), also known as the ‘Titan’, is a symphonic portrait of a ‘hero’ who bears a close resemblance to the young Mahler – a loner who grapples with himself and with the world, whose life struggle ‘dall’inferno al paradiso’, as Mahler called it in an early version, is celebrated only at the last minute with a conquest of self. Yet, remarkably, it is precisely this alter ego that Mahler finishes off in his Second Symphony. ‘I have called the first movement “Todtenfeier” [Funeral Pomp],’ he wrote to the composer and music critic Max Marschalk, ‘and it may interest you to know that it is the hero of my D major symphony who is being borne to his grave, his life being reflected as in a clear mirror. Here, too, the great question is asked: What did you live for? Why did you suffer? Is it all only a vast, terrifying joke? We have to answer these questions somehow if we are to go on living – indeed, even if we are only to go on dying! The person in whose life this call has resounded, even if it was only once, must give an answer. And it is this answer that I give in the last movement.’

The letter to Marschalk gives the impression, between the lines in any case, that Mahler felt he had outgrown the egocentric obsessions of his own heroic years, demonstrably sealing his spiritual evolution with the interment of a former self. The most individual stirrings of the soul in the First Symphony are no match for the seasoned universal questions of humanity in the Second.

Indeed, the transformation is audible. Although he did write one movement of the Second Symphony the same year he completed the First, Mahler proving once again that he is a master of the grotesque, the Second Symphony lacks the impetuous, eccentrically ambiguous elan of its predecessor, which with all its pathos truly was a youthful work. Nearly an hour and a half long and scored for a giant orchestra with a large brass section, Fernorchester, large choir, and soprano and contralto parts, the Second Symphony rivals Beethoven’s Ninth (1823–4). Deliberately and with Beethoven in mind, Mahler transcends the symphonic form, which had become a straitjacket for him in his attempt to express the highest ideas, as he would later tell his friend, the violinist Natalie Bauer-Lechner; ultimately, he had to resort to the use of words, since he simply ‘could not manage any longer with notes alone’.

Two of the five movements contain vocal parts, and a third is based on Mahler’s lied output. The fourth movement (‘Urlicht’) is a lied from Des Knaben Wunderhorn, the early nineteenth-century German folk song anthology that left an indelible mark on Mahler’s lieder and symphonies. The third movement, a scherzo, is an instrumental version of Mahler’s hilarious Wunderhorn lied Des Antonius von Padua Fischpredigt, in which St Anthony preaches to the fish with naive and pointless devotion – a wasted effort indeed, given that his congregation proves to be as deaf as the human variety. Following an earth-shattering musical rendering of Judgement Day, the colossal choral finale concludes with a setting of Klopstock’s hopeful ‘Resurrection’ ode.

The means deployed are complementary to the work’s thematic breadth. The narcissistic ‘Sturm und Drang’ of the First Symphony is relentlessly overcompensated for by an emphasis, lovingly placed, on the human condition. The misunderstood artist has become a humanist who, out of compassion, ponders the plight of his fellow man, and like a brother in distress, whispers a message of hope in his ear on Klopstock’s wings, promising resurrection and immortality. Mahler’s missionary zeal is so great that he even adds a few of his own lines of consoling verse to Klopstock’s text: ‘O glaube: Du wardst nicht umsonst geboren! Hast nicht umsonst gelebt, gelitten!’ (O believe, You were not born for nothing! Have not lived for nothing, Nor suffered!) The hero of the First Symphony is buried because a new one has risen up, a man who fraternises with his fellow men.

Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 1 (1884–8), also known as the ‘Titan’, is a symphonic portrait of a ‘hero’ who bears a close resemblance to the young Mahler – a loner who grapples with himself and with the world, whose life struggle ‘dall’inferno al paradiso’, as Mahler called it in an early version, is celebrated only at the last minute with a conquest of self. Yet, remarkably, it is precisely this alter ego that Mahler finishes off in his Second Symphony. ‘I have called the first movement “Todtenfeier” [Funeral Pomp],’ he wrote to the composer and music critic Max Marschalk, ‘and it may interest you to know that it is the hero of my D major symphony who is being borne to his grave, his life being reflected as in a clear mirror. Here, too, the great question is asked: What did you live for? Why did you suffer? Is it all only a vast, terrifying joke? We have to answer these questions somehow if we are to go on living – indeed, even if we are only to go on dying! The person in whose life this call has resounded, even if it was only once, must give an answer. And it is this answer that I give in the last movement.’

The letter to Marschalk gives the impression, between the lines in any case, that Mahler felt he had outgrown the egocentric obsessions of his own heroic years, demonstrably sealing his spiritual evolution with the interment of a former self. The most individual stirrings of the soul in the First Symphony are no match for the seasoned universal questions of humanity in the Second.

Indeed, the transformation is audible. Although he did write one movement of the Second Symphony the same year he completed the First, Mahler proving once again that he is a master of the grotesque, the Second Symphony lacks the impetuous, eccentrically ambiguous elan of its predecessor, which with all its pathos truly was a youthful work. Nearly an hour and a half long and scored for a giant orchestra with a large brass section, Fernorchester, large choir, and soprano and contralto parts, the Second Symphony rivals Beethoven’s Ninth (1823–4). Deliberately and with Beethoven in mind, Mahler transcends the symphonic form, which had become a straitjacket for him in his attempt to express the highest ideas, as he would later tell his friend, the violinist Natalie Bauer-Lechner; ultimately, he had to resort to the use of words, since he simply ‘could not manage any longer with notes alone’.

Two of the five movements contain vocal parts, and a third is based on Mahler’s lied output. The fourth movement (‘Urlicht’) is a lied from Des Knaben Wunderhorn, the early nineteenth-century German folk song anthology that left an indelible mark on Mahler’s lieder and symphonies. The third movement, a scherzo, is an instrumental version of Mahler’s hilarious Wunderhorn lied Des Antonius von Padua Fischpredigt, in which St Anthony preaches to the fish with naive and pointless devotion – a wasted effort indeed, given that his congregation proves to be as deaf as the human variety. Following an earth-shattering musical rendering of Judgement Day, the colossal choral finale concludes with a setting of Klopstock’s hopeful ‘Resurrection’ ode.

The means deployed are complementary to the work’s thematic breadth. The narcissistic ‘Sturm und Drang’ of the First Symphony is relentlessly overcompensated for by an emphasis, lovingly placed, on the human condition. The misunderstood artist has become a humanist who, out of compassion, ponders the plight of his fellow man, and like a brother in distress, whispers a message of hope in his ear on Klopstock’s wings, promising resurrection and immortality. Mahler’s missionary zeal is so great that he even adds a few of his own lines of consoling verse to Klopstock’s text: ‘O glaube: Du wardst nicht umsonst geboren! Hast nicht umsonst gelebt, gelitten!’ (O believe, You were not born for nothing! Have not lived for nothing, Nor suffered!) The hero of the First Symphony is buried because a new one has risen up, a man who fraternises with his fellow men.

Like the first version of the First Symphony (that included ‘Blumine’, which Mahler later discarded), the Second Symphony is a five-movement work that appears to be divided into two Teile or Abteilungen (parts or units). Mahler suggested that they should be separated by at least a five-minute pause. The first Abteilung is made up of the funeral march (Allegro maestoso), originally composed as a self-contained whole; the break is proceeded by the instrumental ländler (Andante moderato) and a scherzo (‘In ruhig fliessender Bewegung’), directly followed by the hymn-like ‘Urlicht’ for solo contralto and the monumental finale.

As Mahler wrote to Marschalk, the first movement, sketched in September 1888, originally bore the name ‘Todtenfeier’. As he had done with the First Symphony, Mahler called it a ‘symphonic poem’, albeit only after having crossed out the original title ‘Symphony in C minor’. According to statements he made to Natalie Bauer-Lechner, Mahler had made sketches of the Scherzo and Andante in Leipzig earlier in 1888, which he developed in Steinbach in 1893. Yet it was not until March 1894 that the symphony actually evolved into a fully fledged work. It was during the great conductor Hans von Bülow’s memorial service in Michaelskirche in Hamburg that Mahler heard Klopstock’s poem ‘The Resurrection’, which provided him with the revelation he needed to overcome his artistic and philosophical impasse. A few months later, on 25 July 1894, Mahler could write to his friend Arnold Berliner to tell him that he had completed the finale, saying, ‘Es ist das Bedeutendste, was ich bis jetzt gemacht habe’ (It is the greatest thing I have done so far).

Without yielding to the drudgery of the symphonic tradition, Mahler seems to seek a connection with his musical predecessors, more so than he had done in the First Symphony. The model of the choral symphony, explicitly borrowed from Beethoven, is one example, just as the technique of motivic fragmentation that emerges in the Second is frequently reminiscent of Beethoven. Echoes of Bruckner and Wagner are clearly audible. In the finale, Mahler combines the Dies irae theme – which Berlioz had used in his Symphonie fantastique (1830) – with the clamorous pandemonium in the orchestra depicting the Resurrection, followed by blasts in the brass featuring the trumpets of the apocalypse, headed ‘Der grosse Appell!’ (The grand summons!) in the manuscript. With all its show of genius, this is unadulterated figurative programme music.

All the more impressive is Mahler’s ability to incorporate a profusion of atmospheres and idioms (e.g. march, chorale, ländler, Naturlaut and lied) into a symphonic form in which extreme dramatic contrasts bolster, rather than weaken, the unity of the work. At first glance, the five movements are like neighbouring, yet independent, republics on a vast, savage symphonic continent. They are worlds apart in terms of their respective length, instrumentation and tone. Although constructive elements like tonal and thematic relationships underpin either covertly or audibly their latent coherence, it is primarily the all-pervasive idea of the horror of death which holds this enormous work together. This fear ultimately becomes so unbearable that it is man’s steadfast belief in an escape which is his only consolation.

Translation: Josh Dillon

Like the first version of the First Symphony (that included ‘Blumine’, which Mahler later discarded), the Second Symphony is a five-movement work that appears to be divided into two Teile or Abteilungen (parts or units). Mahler suggested that they should be separated by at least a five-minute pause. The first Abteilung is made up of the funeral march (Allegro maestoso), originally composed as a self-contained whole; the break is proceeded by the instrumental ländler (Andante moderato) and a scherzo (‘In ruhig fliessender Bewegung’), directly followed by the hymn-like ‘Urlicht’ for solo contralto and the monumental finale.

As Mahler wrote to Marschalk, the first movement, sketched in September 1888, originally bore the name ‘Todtenfeier’. As he had done with the First Symphony, Mahler called it a ‘symphonic poem’, albeit only after having crossed out the original title ‘Symphony in C minor’. According to statements he made to Natalie Bauer-Lechner, Mahler had made sketches of the Scherzo and Andante in Leipzig earlier in 1888, which he developed in Steinbach in 1893. Yet it was not until March 1894 that the symphony actually evolved into a fully fledged work. It was during the great conductor Hans von Bülow’s memorial service in Michaelskirche in Hamburg that Mahler heard Klopstock’s poem ‘The Resurrection’, which provided him with the revelation he needed to overcome his artistic and philosophical impasse. A few months later, on 25 July 1894, Mahler could write to his friend Arnold Berliner to tell him that he had completed the finale, saying, ‘Es ist das Bedeutendste, was ich bis jetzt gemacht habe’ (It is the greatest thing I have done so far).

Without yielding to the drudgery of the symphonic tradition, Mahler seems to seek a connection with his musical predecessors, more so than he had done in the First Symphony. The model of the choral symphony, explicitly borrowed from Beethoven, is one example, just as the technique of motivic fragmentation that emerges in the Second is frequently reminiscent of Beethoven. Echoes of Bruckner and Wagner are clearly audible. In the finale, Mahler combines the Dies irae theme – which Berlioz had used in his Symphonie fantastique (1830) – with the clamorous pandemonium in the orchestra depicting the Resurrection, followed by blasts in the brass featuring the trumpets of the apocalypse, headed ‘Der grosse Appell!’ (The grand summons!) in the manuscript. With all its show of genius, this is unadulterated figurative programme music.

All the more impressive is Mahler’s ability to incorporate a profusion of atmospheres and idioms (e.g. march, chorale, ländler, Naturlaut and lied) into a symphonic form in which extreme dramatic contrasts bolster, rather than weaken, the unity of the work. At first glance, the five movements are like neighbouring, yet independent, republics on a vast, savage symphonic continent. They are worlds apart in terms of their respective length, instrumentation and tone. Although constructive elements like tonal and thematic relationships underpin either covertly or audibly their latent coherence, it is primarily the all-pervasive idea of the horror of death which holds this enormous work together. This fear ultimately becomes so unbearable that it is man’s steadfast belief in an escape which is his only consolation.

Translation: Josh Dillon

Biografie

Budapest Festival Orchestra, orchestra

In 1983, Iván Fischer made a dream come true when he and Zoltán Kocsis founded the Budapest Festival Orchestra. From its very beginning, the Hungarian company’s ambition was to offer performances of the highest level and to serve the public in different ways.

The orchestra is famous for its innovative programming, including surprise concerts and musical marathons.

The Budapest Festival Orchestra performs regularly in major concert halls including The Concertgebouw, where they played Mahler’s Ninth Symphony in 2013, Carnegie Hall and Lincoln Center in New York, the Musikverein in Vienna and the Royal Albert Hall in London.

The orchestra was nominated for a Grammy Award in 2013 for their CD of Mahler’s First Symphony. A year later the Budapest Festival Orchestra won a Diapason d’Or and the Italian ‘Toblacher Komponierhäuschen’ prize for their recording of his Fifth Symphony.

Netherlands Radio Choir, choir

The Netherlands Radio Choir, founded shortly after the Second World War, is the only professional choir in the Netherlands devoted to the large symphonic choral repertoire.

The choir is closely affiliated with the Dutch public broadcasting system NPO and sings frequently in several series: the NTR Saturday Matinee, The Sunday Morning Concert and AVROTROS Friday concert series.

Their repertoire spans contemporary music (commissioned works by Dutch and other composers), older works from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and opera. The Netherlands Radio Choir sings frequently with world-renowned orchestras, joining the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra and the Concertgebouw Orchestra, with whom they have a long and fruitful association, for the broadcast series.

The Radio Philharmonic Orchestra and the Radio Choir shared the 2017 Concertgebouw Prize. Since 2020, their Chief Conductor has been Benjamin Goodson.

Iván Fischer, conductor

Iván Fischer studied piano, violin, cello and composition in Budapest before studying conducting with Hans Swarowsky and Nikolaus Harnoncourt in Vienna and Salzburg. Fischer is the founder and Chief Conductor of the Budapest Festival Orchestra, and Honorary Conductor of Berlin’s Konzerthausorchester and Konzerthaus, where he was Chief Conductor between 2012 and 2018.

Since 2018 he has been the Vicenza Opera Festival’s Artistic Director, and since 2021-2022 has been an Honorary Guest Conductor with the Concertgebouw Orchestra. He is a frequent guest with the Berliner Philharmoniker, New York Philharmonic and other leading orchestras. He has conducted opera productions in the Wiener Staatsoper, London’s Royal Opera House Covent Garden, the Opéra de Paris and others.

Fischer is the founder of Hungary’s Gustav Mahler Society and patron of the British Kodály Academy. In 2013 he became an honorary member of the Royal Academy of Music in London.

Christiane Karg, soprano

Christiane Karg, born in Bavaria, studied with Heiner Hopfner and Wolfgang Holzmair at Salzburg’s Universität Mozarteum and took part in the Staatsoper Hamburg’s Internationale Opernstudio. From 2008 to 2013, she was a member of the ensemble at Oper Frankfurt.

While still studying, Karg made her debut at the Salzburger Festspiele.

She has performed in the major opera houses such as London’s Royal Opera House Covent Garden, Milan’s La Scala, Wiener Staatsoper and The Metropolitan Opera in New York. Recently she sang Mahler’s Rückert-Lieder with the Bamberger Symphoniker conducted by Andrés Orozco-Estrada, and his Fourth Symphony with the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig and its Chief Conductor Andris Nelsons.

The soprano made her Concertgebouw debut in 2013 in the Recital Hall.

Anna Lucia Richter, mezzo-soprano

Anna Lucia Richter first performed in the girls’ choir of the Dom cathedral in Cologne. Her first lessons were with her mother, Regina Dohmen, and she studied later with Kurt Widmer and Klesie Kelly-Moog, as well as with Margreet Honig, Edith Wiens and Christoph Prégardien.

The singer has won a string of prizes, among them a Borletti-Buitoni Trust Award in 2016.

From the spring of 2020 she was guided by Tamar Rachum in the transition from soprano to mezzo-soprano, an important step rich in new opportunities. She was the alto soloist in Mahler’s Second Symphony with the Bamberger Symphoniker, conducted by Jakub Hrůša.

Her repertoire reaches from Monteverdi and Bach, and late-Romantics such as Mahler and Berlioz, to contemporary composers such as Holliger and Rihm.

Richter made her Concertgebouw debut in 2014 in the Recital Hall, and she has appeared there and in the Main Hall many times since then.